7. Well-Designed Student Privacy Laws Provide Resources

Well-designed student privacy legislation considers the support necessary to implement student privacy requirements and proactively provide those resources. This support can take various forms, such as designating privacy personnel at the state level, offering training resources, providing model policies for schools to use, and allocating funding. It is crucial for policymakers to ensure that appropriate resources are included in student privacy bills so that schools can comply with privacy requirements without diverting resources from providing quality education to students.

Utah’s student privacy law is a fantastic example of how states can incorporate resource provisions into their student privacy laws. One of the keys to Utah’s success is the provision of ongoing funding.19 Utah’s legislation required the SEA to create supporting staff roles and provide services to LEAs, but did not fund such activities until the newly-hired chief privacy officer went to the legislature and asked for the funding that would be needed to support those services. As observed by another state,20

“Utah’s Student Privacy and Data Protection Act...notably included a funding component to implement the requirements of the law. The law provides Utah’s State Education Agency with dedicated student privacy staff that are equipped to provide technical assistance to local education agencies and continuously develop resources such as model contracts. One specific role created is that of the Student Data Privacy auditor, who periodically reviews district data governance plans to ensure alignment with the law.”

Utah also exemplifies how state policymakers can require privacy training for all school officials who may access student data. Utah not only mandates such training, but also provides mechanisms to identify who needs student privacy training and a documentation requirement upon completing the training. For example, Utah Code Ann. 53E-9-204 requires schools to “create and maintain a list that includes the name and position of each school employee who the public school authorizes…to have access to an education record” without consent from parents or students. School boards must then “provide training on student privacy laws” to every employee on that list, and those individuals must provide a signed statement that “certifies [they] completed the training…and that [they] understand[] student privacy requirements.” By comprehensively identifying who must be trained on student privacy and then requiring those employees to certify that they received the training, Utah’s law ensures that all employees with access to student data have the necessary resources and awareness to understand student privacy requirements.

8. Well-Designed Student Privacy Laws Have Clear Data Governance Requirements and Restrictions

Well-designed student privacy legislation requires stakeholders to implement data governance policies that reflect and facilitate the requirements of FERPA, state-level privacy protections, and student privacy best practices. Data governance consists of the crucial processes and infrastructure an organization puts in place to establish and enforce privacy safeguards to protect student data, from the original decision to collect student data to its eventual destruction. This includes creating comprehensive privacy and security policies that define roles and responsibilities for those with access to the data and restrict the use and disclosure of student data, along with other key privacy considerations. State policymakers should ensure that their student privacy legislation requires schools and third parties to have data governance practices sufficient to ensure strong protections for student data.

There’s no reason to reinvent the wheel.

Data Governance Requirements and Restrictions for Schools

State legislation should compel schools to enact data governance policies without being overly prescriptive or creating onerous requirements that unnecessarily burden schools. This balanced approach involves requiring schools to adopt data governance practices to achieve certain standards and outcomes, without dictating which methods the state uses to do so whenever possible. State policymakers should allow schools the flexibility to craft policies tailored to their unique needs and circumstances, empowering them to take ownership of data governance in a way that best aligns with their educational goals and community standards. At the same time, it is important that schools not be burdened with data governance responsibilities without adequate support.

Multiple states require that schools adopt data governance policies. For instance, California requires each school district to establish written policies and procedures to secure pupil records and ensure authorized access (5 CA Code of Regs 431). Data governance policies should address the following tasks and activities:

- Data collection, transport, storage, security, retention, and deletion policies;

- For example, Oklahoma limits the student data districts can give to the SEA, restricts access to student data, defines circumstances in which data can leave the state, and requires the SEA to develop a data security plan (Ok. Stat. tit. 70 § 3-168).

- Who is permitted to access student information and the circumstances under which it can be shared, including specific policies regarding law enforcement requests;

- For example, Illinois specifies the types of individuals and entities that schools may share student data with and limits all other sharing unless the school has a written agreement (105 Ill. Comp. Stat. 85/26).

- Training requirements for anyone who accesses student data;

- Designated contacts to address privacy inquiries and manage requests for accessing student records;

- For example, New York requires education agencies to designate an officer to serve as the point of contact for data security and privacy (N.Y. Comp. Codes R. & Regs. tit. 8 § 121.8)

- Incident response plans (more details on this below).

- For example, Colorado requires schools and edtech contractors to have information protection or security programs. (Colo. Rev. Stat. § 22-16-107)

Colorado’s approach to data governance provides a good example. Schools are required to adopt a student information privacy and protection policy that, at a minimum, meets the same standards as those in the Department of Education’s guidance. These standards include security breach planning, notice, and procedures; data retention and destruction procedures; and data collection and sharing procedures (Colo. Rev. Stat § 22-16-106).

Data Governance Requirements and Restrictions for Third Parties

Many states focus legislation on what third parties, such as vendors and researchers, can and cannot do with student data. It is important that provisions governing third parties adequately protect student data while not creating overly stringent restrictions that may inadvertently have negative impacts on students and schools. For example, states that sought to increase security by prohibiting student data from being carried student data on "portable media devices" inadvertently prohibited the use of cameras in schools.25 Additionally, provisions meant to restrict vendors may inadvertently restrict education researchers too, negatively impacting research that can be critical to identifying effective learning approaches.

To safeguard student data and ensure that data is only used for its intended purpose, well-designed student privacy legislation should require schools to enter into written agreements with any third-party vendors that receive student data.

- Prohibiting the collection or use of student data for noneducational purposes, such as to develop marketing profiles, advertising, or sales purposes;

- Requiring proactive steps to protect student data from unauthorized access and safeguarding students’ data against breaches;

- Requiring student data to be destroyed or sufficiently deidentified at the conclusion of the contract or agreement (particularly as more vendors incorporate AI into their products, thus creating more risk).

We also recommend including these requirements:26

- Require third parties to enter into written agreements with education agencies and institutions before they receive PII.

- For example, several states, including Connecticut and Idaho require that third parties enter into written agreements with education agencies before receiving student data. (Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10-234bb; Idaho Code § 33-133)

- Restrict third parties from collecting, using, retaining, or sharing student data for noneducational purposes, including selling the data and building student profiles to inform advertisements.

- For example, Georgia, Illinois, and New Hampshire, among others, prohibit vendors from selling student data or using student data to engage in targeted advertising or create profiles (Ga. Code Ann. § 20-2-666; 105 Ill. Comp. Stat. 85/10; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 189:68-a)

- Limit the student data available to third parties to the minimum amount of data required to fulfill their duties;

- Require third parties to be transparent about data collection, use, sharing, retention, and storage to help build trust in the student data lifecycle;

- For example, Virginia requires third parties to maintain transparency around student data collection and information security (VA Code Ann. § 22.1-289.01)

- Require third-party staff who receive student data to undergo training that ensures they know how to responsibly, legally, ethically, and equitably use, protect, and secure student data; and

- For example, New York requires contracts with third-parties to specify how third parties are trained on the federal and state laws governing confidentiality of student data prior to receiving access (N.Y. Comp. Codes R. & Regs. tit. 8 § 121.6)

- Establish reasonable penalties and consequences for third parties that fail to comply with student privacy requirements.

- For example, Nevada requires contracts between an educational entity and a service provider to include a penalty for any breach of contract, including but without limitation, termination of contract and payment for any monetary damages (Nev. Rev. Stat. § 388.272)

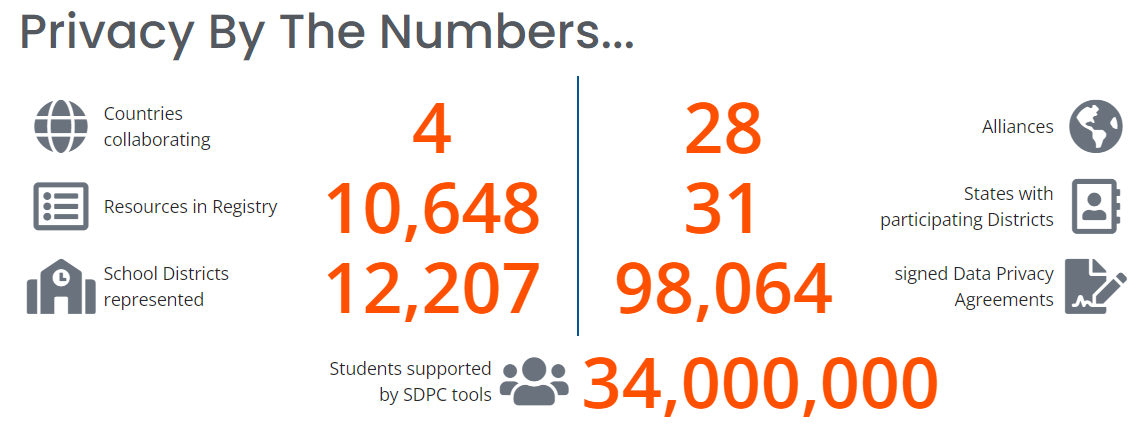

The Student Data Privacy Consortium

At Cambridge Public Schools, Steve Smith and his team created their own data privacy agreement that vendors must agree to in order to partner with the schools. Smith then went beyond his district to create the Student Data Privacy Consortium (SDPC),27 a collaboration among schools, districts, education agencies, policymakers, and edtech and other companies to find real-world, adaptable, and implementable solutions to growing data privacy concerns. SDPC has district or state members in 31 states as of June 2024.28 Each state has its own privacy contract addendum, and SDPC has used its leverage––the number of districts that press vendors to sign the addendum in order to do business in their schools––to get top edtech companies to also sign the addendum. SDPC also provides a public database that shows which edtech tools are being used in which member districts, whether edtech companies have signed the agreement, and provides a link to signed agreements. In July 2020, SDPC released the first National Data Privacy Agreement (NDPA) to streamline application contracting and set common expectations between districts and marketplace providers.29

9. Well-Designed Student Privacy Bills Facilitate Safe Use of Data

The deliberate and thoughtful use of education data has great potential to improve student outcomes. Student data is key to fulfilling many beneficial outcomes, such as personalizing learning experiences, improving instructional strategies, and engaging in evidence-informed policymaking.30 For example, an analysis of student data found racial disparity in school discipline, with black students facing disproportionately higher rates of suspension and expulsion compared to white students, which prompted the Secretary of Education and Attorney General to issue recommendations for districts to make the discipline process more fair.31 Additionally, accessible student data can inform changes at the local level, as seen by Chicago schools’ project to increase graduation rates and college enrollment.32

However, policymakers must account for the reality that, as the usefulness of datasets to gain insights increases, there is often a corresponding decrease in privacy protections and vice versa. While collecting more detailed and accessible data can lead to greater insights, it also increases the risk that sensitive data will be exposed or students could be re-identified. Well-designed student privacy legislation must find a delicate balance between allowing for beneficial data uses and safeguarding student information. Student data collection must be thoughtfully and carefully tailored to ensure that both students and parents are confident that information is protected. State policymakers must ensure that legislation promotes student privacy and data utility, ideally maximizing for both.

These examples illustrate how states can harness the power of education data to support student success and research for evidence-informed policymaking, all while respecting and protecting student privacy. The careful balancing of privacy concerns with the benefits of data use in the educational context is paramount. By creating SLDSs with robust privacy protections and creating meaningful policies governing researcher data access, policymakers can ensure that student data serves its intended purpose of improving educational practices while maintaining the highest standards of privacy.