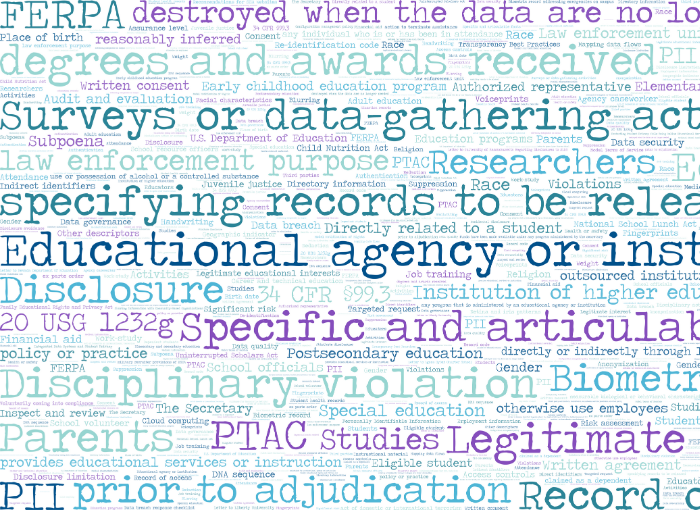

Enhancing EdTech Accountability

June 2024

Katherine Kalpos, Morgan Sexton, Amelia Vance, and Casey Waughn

CC BY-NC 4.0

Sharing student data with a 4th grade teacher, Mr. Stevens, so he can tailor his lesson plans for the upcoming school year?

Use the school official exception.

Sharing student data with an edtech company to create student profiles on a new app that customizes lessons based on students’ strengths and weaknesses?

Use the school official exception.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, schools must use the same exception to FERPA’s consent requirement in order to share student data with teachers and with edtech companies. This leads to both confusion and inadequate student privacy protections. To remedy this, FERPA needs a statutory change to add more accountability safeguards for sharing student PII with technology companies. We suggest modifying the current statute to establish distinct exceptions: one for school staff (and their helpers inside schools), and another for third parties outside schools.

FERPA states that no one other than parents and eligible students can access student personally identifiable information (PII) in education records unless they have consent or an exception to FERPA’s consent requirement applies. So, while they may not realize it, teachers rely on FERPA’s school official exception to access student data for everyday instructional and administrative use. The school official exception was broadened in 2008 to also cover schools’ sharing of data with third-party companies providing institutional services, like student information systems (SIS), to the school as long as additional requirements (such as “direct control”) are met.

While it's important for schools to be able to share student data with both teachers and edtech companies for educational purposes, the current structure under FERPA creates perception risks for education systems and practical risks for students. Sharing data with edtech companies under the same exception as that used for schools undercuts communities’ trust in schools because it fuels the myth that companies can do whatever they want with student data. It may also mean that student data is not adequately protected by those companies, as this contributes to the perception that companies are not regulated under FERPA. There is currently no clear guidance on what “direct control” means in practice, there are no standard security requirements that edtech vendors must meet before receiving student data, and edtech companies are not required to have written contracts with schools that use their products. In addition, many schools lack the knowledge and resources to initiate, let alone negotiate, such contracts.

Below we outline the context of the problem and detail a suggested statutory amendment to resolve it.

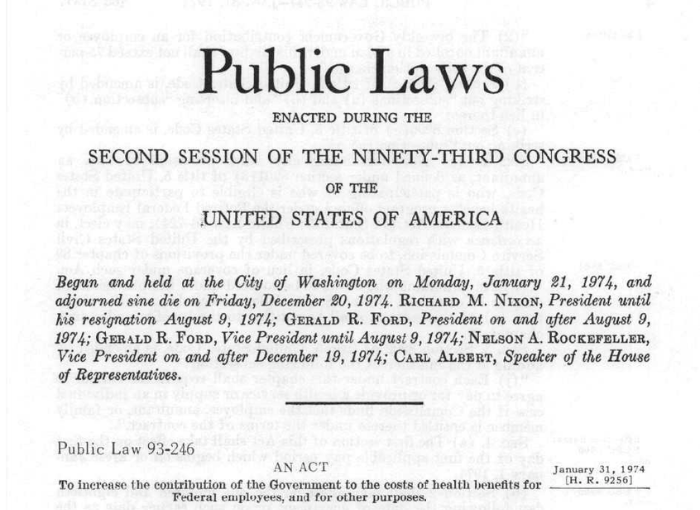

Evolution of FERPA's School Official Exception

When FERPA passed in 1974, it included an exception allowing schools to disclose FERPA-covered data to “other school officials…who have been determined by such agency or institution to have legitimate educational interests” without consent from parents or eligible students (34 CFR 99.31(a)(1)(i)(A)). This was primarily used to share student data internally with teachers, school staff, and volunteers without consent in daily educational encounters. The exception requires schools to “use reasonable methods to ensure that school officials obtain access to only those education records in which they have legitimate educational interests” (34 CFR 99.31(a)(1)(ii)). While “legitimate educational interests” isn’t defined in the exception, the Department of Education (USED) describes the term in a model FERPA notice as follows: “A school official typically has a legitimate educational interest if the official needs to review an education record in order to fulfill his or her professional responsibility.” For example, while an English teacher may have a legitimate educational interest in reading students’ personal essay assignments to grade them, a math teacher at the same school would not have a legitimate educational interest in reviewing those same essays.

The 2008 FERPA regulations expanded this exception to also cover disclosures to external “contractor[s], consultant[s], volunteer[s] or other part[ies]” to whom the school “outsourced institutional services or functions” (34 CFR 99.31(a)(1)(i)(B)). In addition to the existing “legitimate educational interests” requirement, the 2008 regulations added that third parties seeking to qualify as school officials must meet the following criteria:

- Perform an institutional service or function that the school would otherwise use employees for;

- Be under the school’s direct control regarding the use and maintenance of education records; and

- Be subject to the use and redisclosure requirements in 34 CFR 99.33(a). 34 CFR 99.31(a)(1)(i)(B)(1)-(3)

This enabled schools to share data much more broadly with third parties outside of the school by using the school official exception–a change that was helpful (and arguably necessary) for schools seeking to incorporate edtech into the classroom. However, adding this to an existing exception designed to share data internally within the school environment did not account for the unique underlying risks associated with sharing student data externally.

Accountability Issues for Technology Companies Receiving Student Data

Despite massive differences in schools’ relationships with teachers and with technology companies, the 2008 regulations added only three new requirements to the school official exception for disclosures to service providers, as noted above. These restrictions are generally confirmed in contractual agreements between schools and their third-party service providers, which can be either a written contract or click-through terms of service if those terms allow the school to maintain direct control. Unfortunately, there is no formal definition or even informal guidance on what constitutes “direct control.” However, we compiled the following list by interpreting USED’s guidance that indicates what would not be considered direct control:

A school does not retain direct control if their contract or terms of service say the company may do the following:

- Modify the terms of agreement at any time without notice or consent from the school or district;

- Use student data to market or advertise to students or their parents or mine or scan data and user content for the purpose of advertising or marketing to students or their parents;

- Use data for any purpose other than the purpose for which the data was originally provided to the service provider without notice to users;

- Use student personally identifiable information after it is no longer needed or after the school or district requires that that information be deleted;

- Not require their subcontractors to adhere to the service provider’s terms of service;

- Collect data about the student from a third-party source if the student logs into the service through a third-party website, such as a social networking site;

- Share student personal information that the user is not knowingly providing to the service, such as metadata that may be personally identifiable;

- Share de-identified information but defines de-identification too narrowly;

- Claim ownership over the student data or copyright or a license to use student data or uploaded school or student user content;

- In any way limit the school or district’s access to student information when requested;

- Not mention security protections.

But what if the school doesn’t have a written agreement with an edtech company providing a product that is used in classrooms? While we can make several educated guesses about what direct control would mean, the unfortunate reality is that we don’t have authoritative guidance on how to evaluate direct control without a written agreement. The school official exception does not require schools to have a contract with third-party service providers with whom they share data, though it is best practice to have one and many schools do. Moreover, guidance from USED only references direct control in a scenario in which a written agreement exists. This gap can lead to serious accountability problems when schools do not have written agreements with companies that explicitly state the safeguards that must be in place to protect student data under the school official exception.

This risk is that much greater when the school uses a technology that was not designed for educational uses. For example, when schools quickly transitioned to remote learning at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many educators turned to video conferencing software to conduct virtual classes despite those platforms not being designed for use with children or for K-12 educational settings. Additionally, companies offering technologies aimed at general audiences are often not covered by state law requirements for edtech companies. In such cases, schools have limited to no bargaining power to require privacy protections since these companies did not intend for schools to use their product. Some sector-specific laws may apply to protect some student data, like the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), which requires companies to obtain parental (or sometimes the school’s) consent before collecting personal information from children under 13. But since the U.S. does not have a comprehensive underlying privacy law, student data processed by these companies often receives no protections unless the company has voluntarily adopted them (for example, through a privacy policy). This can mean that certain products, such as apps providing information or access to academic journals, are either not accessible to students at all or (more likely) are being used by students without adequate privacy protections in place. For this reason, it is crucial that schools have written agreements with technology service providers to establish required privacy safeguards and to ensure that the companies are legally restricted from doing whatever they want with student data.

Companies are Different and Need Separate Rules

Commercial Motives

Student data “holds considerable commercial value outside the school context and apart from education purposes,” creating an incentive for vendors to commercialize student information for their own benefit. As student privacy scholar Elana Zeide explains, for-profit companies are often viewed with skepticism because there is concern that they might focus more on making money than on advancing students' educational needs. Most edtech providers handling student data are for-profit companies. This is in sharp contrast to the traditional education landscape of public and non-profit educational institutions and supporting services, which are explicitly oriented and legally bound to education-oriented missions.

While educators and school administrators are primarily focused on students' educational interests and wellbeing, for-profit companies often have additional, competing interests in maximizing their profits–which may come at the cost of sacrificing key student privacy protections.

Proximity to Students

As internal actors within the school system, teachers have a direct relationship with students and are physically present in the classroom setting. On the other hand, edtech companies operate outside of the school environment, resulting in less direct contact with students and likely no personal relationship with them. This difference in proximity can significantly impact the potential consequences of sharing student data, as detailed by Elana Zeide:

“Traditionally, the individuals who evaluated and made decisions about students were close at hand and relied on personal, contextualized observation and knowledge. Parents, students, or administrators with concerns about particular outcomes could go directly to the relevant decision maker for explanation. This created transparency, and an easy avenue to seek redress, thereby providing accountability.”

But this dynamic changes when student data is shared with external companies. As algorithms increasingly drive decisions, the traditional role of in-person decision makers shifts to obscure and distant technologies.

The physical presence of teachers allows for easier accessibility in case of any misuse or mishandling of student data. The opposite holds true for external vendors, making it more difficult to exercise accountability mechanisms regarding their student data practices.

Contracting Hurdles for School Districts

Why don’t schools counter the risks associated with sharing data with vendors through contractual safeguards? It is best practice for schools, before using tech companies’ products with students, to enter written agreements with the companies to ensure the company will abide by the school’s privacy policies and to build community trust in the school’s responsible use of technology. That said, the process of actually executing these written agreements can be very challenging for schools in practice.

The U.S. education system is rooted in the concept of “local control,” which is the idea that school districts should be able to make decisions impacting their communities. This means that individual districts often each individually bargain with companies about their terms of service and any contractual provisions. School personnel often don’t have the expertise or the resources they need to negotiate a vendor’s boilerplate contractual language, which can leave the school in somewhat of a David-and-Goliath situation whenever they want to use new edtech. Even when a coalition of districts collectively bargain, some companies are simply so powerful - such as standardized testing companies, email or cloud providers, or companies that provide significant curricular materials - that districts may not have the market power to get the changes they need in written agreements to comply with FERPA. Furthermore, it can be extremely difficult for schools to determine what should or should not be included in these contracts to make them FERPA compliant. FERPA is notoriously complicated and easily misinterpreted due to its many provisions and clarifications.

FERPA’s answer to that dilemma is simple but infeasible in practice: the school should not contract if their agreement with the company would violate FERPA’s requirements. Many schools had already implemented edtech by the time USEd released guidance on FERPA obligations related to edtech, and ending the use of products that schools relied on was practically and politically unfeasible. Once schools have built certain school functions dependent on the use of certain edtech, a new understanding of a company’s privacy protections or a change to the company’s terms of service is often not sufficient to justify the school spending money and staff time to switch products.

Schools also often don’t have the money, market power, time, or expertise to shop around until they find an edtech company with a clearly FERPA-compliant privacy policy. Traditional school procurement processes can be extremely time-consuming, requiring thorough evaluations for each product under consideration and numerous staff members dedicated to that task. Procuring edtech can be even more time consuming due to the vetting process. There is not much competition in the edtech space (which only strengthens vendors’ market power), and existing companies often use similar privacy policies with vague contractual terms that could but don’t clearly comply with FERPA. This tends to put schools in a position in which they are forced to choose between forgoing the services they need due to what they see as privacy red tape or dealing with potential FERPA consequences later on. Because of the widespread misconception that FERPA is toothless and that privacy reviews often take significant time to complete, some individual educators or schools have chosen to take on the privacy risk so they can incorporate technologies that they strongly believe will help their students. Unfortunately, this can leave student data exposed to commercialization and misuse.

A Possible Solution

Sharing student data with teachers and with technology companies are both important to the educational process, but FERPA should not allow for both types of data sharing to happen under the same exception. Instead, a separate exception should be created within FERPA to create appropriate requirements and consequences appropriate to the specific risks associated with external companies accessing student data. This change needs to be statutory: Congress should formally amend the FERPA statute to reflect that disclosures to school officials and edtech companies must take place under two separate exceptions. Adding this language directly in the statute will make it easier for school administrators and other stakeholders to find all requirements for this new exception together in one place.

The FERPA statute should be amended to separate the school official exception into two different exceptions, including:

- The school official exception as originally written and intended when FERPA was passed in 1974 to address sharing data with individuals employed by the school and individual volunteers; and

- A separate exception for sharing FERPA-protected data with third-party contractors, including technology companies (such as edtech companies) and any other individual not employed by the school to which the school has outsourced institutional services or functions.

The new exception created specifically for service providers should include, along with the original school official exception requirements, additional safeguards to protect students against the unique circumstances and risks associated with sharing student data with companies.

Additional safeguards in the new exception for sharing data with third party contractors should require the following provisions, at a minimum:

- Require third parties to enter into written agreements with education agencies and institutions before they receive PII. Schools must ensure that the third parties they plan to share PII with are contractually obligated to follow the schools’ privacy standards before sharing PII with them, as in Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10-234bb. This safeguard is especially important when a tool was not designed specifically to be used in schools (for example, a technology designed for general consumer use) because the company’s default privacy practices may violate FERPA.

- Restrict third parties from collecting, using, retaining, or sharing student data for noneducational purposes, including selling the data and building student profiles to inform advertisements. In written agreements with companies, schools should be required to specify an educational purpose for the data sharing and prohibit all secondary uses of educational data. See Kan. Stat. Ann. § 72-6314(c) for an example of this safeguard in state statute.

- Limit the student data available to third parties to the minimum amount of data required to fulfill their duties. Schools should give companies only the minimum amount of student data necessary for the company to fulfill the educational purpose that is specified in the written agreement. This safeguard aligns with the Fair Information Practice Principle of data minimization, which directs entities to collect only PII directly relevant and necessary to accomplish a specified purpose and to retain the PII only for as long as necessary to fulfill the purpose.

- Require third parties to be transparent about data collection, use, sharing, retention, and storage to help build trust in the student data lifecycle. As in Utah Code 53E-9-309(2), there should be a list of required provisions to include in written agreements with third parties receiving student data to make things clearer and easier for technology vendors and schools. That list should incorporate provisions discussed in USED’s prior guidance. There should be clear limitations on the use of student data, including whether a company can redisclose student data (this could include a recordation requirement). Additionally, schools should be required to make a record that is accessible under FERPA each time that student PII is shared with companies.

- Require third-party staff who receive student data to undergo training that ensures they know how to responsibly, legally, ethically, and equitably use, protect, and secure student data. Anyone who can access student data should be required to complete student privacy training that is context- and role-specific. This training should cover how to safeguard student data in their role and how to properly limit its use and further disclosure. Some states already require third parties to undergo certain training. For example, New York requires written agreements between schools and companies to specify how employees and assignees who access student data will be trained on the relevant laws governing the data before they receive access (see 8 NY C.R.R. Part 121, §121.6(a)(4)).

- Establish reasonable penalties and consequences for third parties that fail to comply with student privacy requirements. There should be at least one entity that is explicitly tasked with enforcing a third party’s student privacy requirements. For example, New York Education Law Section 2-D.7 explicitly delegates enforcement authority to the chief privacy officer to “investigate, visit, examine and inspect the third-party contractor’s facilities and records and obtain documentation from, or require the testimony of, any party relating to” official complaints or allegations of improper education data disclosure. Entities tasked with enforcement should be able to conduct investigations and set appropriate fines or sanctions directly on third parties for noncompliance, similar to how California’s Student Online Personal Information Protection Act (SOPIPA)––the first student privacy law governing vendors, versions of which have been passed in more than 30 states––“puts responsibility for protecting student data directly on industry."

Closing Thoughts

In today’s schools, students routinely use edtech products to learn, and schools use them to perform daily administrative functions as well as to teach students. This sharing of student data with third parties is very different from the data sharing encompassed by FERPA’s original school official exception. To protect student data adequately, FERPA should better reflect this new context, and policymakers should therefore amend the law to create a separate exception for sharing FERPA-protected data with third-party contractors.

Pingback: Fixing FERPA: Increasing Transparency to Make FERPA’s Privacy Protections More Meaningful – Public Interest Privacy Center