Supreme Court Upholds Age Verification: A Game-Changer for Child Online Safety Laws

July 1, 2025

Jessica Arciniega, Morgan Sexton, & Amelia Vance

CC BY-NC 4.0

Introduction

Last Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a major decision in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, upholding Texas’s law requiring adult websites to verify users’ ages before allowing access. While this case specifically addressed pornographic content, the ruling’s implications likely extend far beyond adult websites—potentially reshaping how courts evaluate the dozens of state laws designed to protect children online that have repeatedly been blocked by federal judges over the past several years.

TLDR:

Paxton fundamentally changes the constitutional landscape for laws protecting children online. By applying intermediate rather than strict scrutiny to age verification requirements, the Court may have opened a pathway for previously blocked child online safety laws to survive constitutional challenges.

Our biggest takeaways?

- Age verification was found to only incidentally burden adults’ ability to access speech that they have a Constitutional right to access, perhaps raising broader existential questions about the future of online anonymity.

- Courts across the country may now apply a more lenient review standard to social media age verification laws, potentially reversing the overwhelming trend (until now) of assuming these laws are fundamentally inconsistent with the First Amendment.

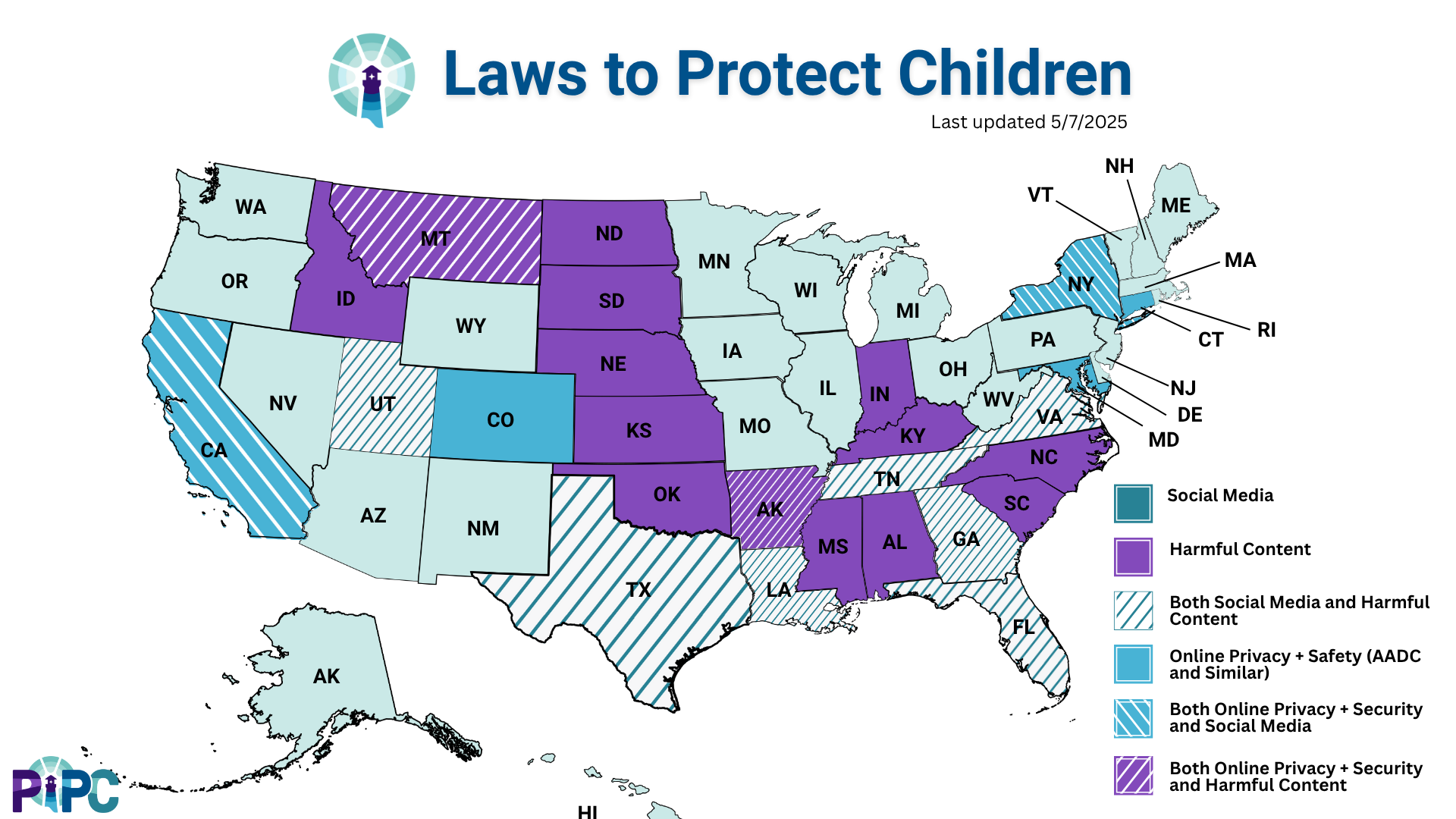

The Current State Landscape

States across the country have been actively passing laws to protect children online, addressing everything from social media access and data collection to exposure to harmful content. However, most of the laws passed that only regulate children’s privacy and/or safety (versus state laws that include special protections for children within a broader consumer privacy law) have faced near immediate legal challenges, with federal courts blocking implementation of such laws while constitutional questions are resolved.

Why Paxton Matters: Changing the Constitutional Rules of the Road

The most significant aspect of this ruling isn’t what the Court decided, but how they decided it. The Court applied “intermediate scrutiny”—a more lenient constitutional standard—rather than the “strict scrutiny” standard that courts have typically used to evaluate laws restricting online speech.

What’s the difference?

Strict Scrutiny:

The government must prove the law serves a “compelling” interest using the “least restrictive means” possible. Most laws fail this test.

VS.

Intermediate Scrutiny:

The government only needs to show the law serves an “important” interest and is “substantially related” to achieving that goal—a much easier standard to meet.

This shift in legal standards could be a game-changer for states trying to regulate online harms to children by making it significantly easier for age verification laws to survive constitutional challenges.

Brief Summary of Paxton

The case challenged Texas’s HB 1181, which requires users to use reasonable age verification methods to verify that an individual is 18+ years old before accessing websites where more than ⅓ of the content is sexual materials “harmful to minors.” The Free Speech Coalition, backed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), argued that forcing users to provide identification violated adults’ First Amendment rights and threatened privacy.

Several justices signaled willingness to uphold the law at oral argument, and today’s 6-3 decision confirmed that approach. The Court found that requiring proof of age to access content that is “obscene to minors” places only an “incidental” burden on adult speech rights.

A Departure from Digital Rights Precedent

This ruling marks the first time the Supreme Court has upheld online age verification as constitutionally valid, representing a significant departure from the Court’s landmark 1997 ruling in Reno v. ACLU. In Reno, the Court applied First Amendment strict scrutiny analysis to strike down parts of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) as overly broad and vague, emphasizing the internet as a uniquely open and democratic medium.

The Court departs from this approach in Paxton. Unlike in Reno, where the Court worried that age verification technology was impractical and would chill adult access, the justices here acknowledged both technological advances and the state’s interest in shielding children from easily accessible online pornography, which has become far more pervasive since the 1990s.

Importantly, the Court distinguished the current Texas law from the CDA by noting that the CDA “swept far beyond obscenity” to regulate much broader categories of content. This distinction matters because it suggests the Court may still be skeptical of laws that regulate non-obscene content—though, as we’ll explore below, the boundaries of this limitation remain unclear.

Implications Beyond Pornography?

The Court’s decision in Paxton may be far-reaching, potentially impacting how we all experience the internet as a whole.

The Social Media Question

While the Texas law specifically targets sites where more than ⅓ is adult content, the Court’s reasoning opens the door to potential broader applications moving forward. However, the Court explicitly said social media is beyond the scope of this decision,* so any extension of Paxton to social media platforms remains speculative at this point.

How might this expand to social media regulation in the future? The Court’s logic could potentially suggest that age verification requirements for social media platforms might be constitutional, particularly if framed around protecting children from harmful content. In footnote 7, the Court even indicated that Texas’s law may not be “facially invalid” even if it required age verification to access all content on a website, including non-obscene material.

That being said, future courts may still distinguish social media platforms by arguing that requiring users to tie their online identities to their real names creates a greater chilling effect on political speech and other strongly protected expression than does requiring identification to access pornography. The application of Paxton’s reasoning to broader online contexts remains an open question that will likely be tested in future litigation.

Impact on Pending Child Safety Laws

This decision arrives at a crucial moment for child online safety legislation. Numerous state laws aimed at protecting children online have recently been blocked or challenged in federal courts, with many cases pointing to precedents from Reno and Ashcroft v. ACLU suggesting that age verification requirements are likely unconstitutional under strict scrutiny analysis.

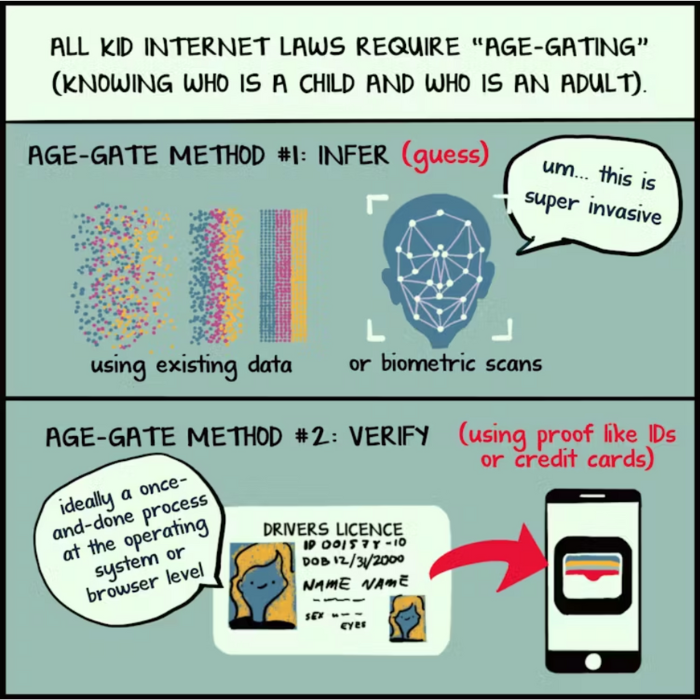

The Court’s switch to using an intermediate scrutiny standard could dramatically change these calculations. Laws that previously seemed to be non-starters under strict scrutiny analysis might now survive constitutional review, provided they:

- Serve an important government interest (protecting children);

- Are substantially related to that goal; and

- Don’t impose excessive burdens on adult users.

Other Laws That May Benefit from Paxton

Age Verification for Social Media: Multiple states have passed laws requiring social media companies to verify users’ ages and obtain parental consent for minor users to use the platform. While these laws regulate broader content than just pornography, Paxton’s reasoning that age verification only incidentally burdens adult users’ access to constitutionally protected speech could potentially apply in this context (though this remains speculative).

Platform Design Requirements: Some laws require platforms to implement age-appropriate design features and/or default privacy settings for minors. While broader than age verification alone, such laws similarly hinge on treating children differently from adults online—an approach that Paxton establishes precedent for.

What the Court Didn’t Address

The majority in Paxton left several key issues unaddressed, specifically those related to the additional privacy risks associated with mandatory age verification online and the potential impact this decision may have on online anonymity.

Inherent Privacy Risks

While the Court addressed First Amendment concerns, it gave relatively little attention to privacy implications of age verification requirements. The majority dismissed privacy concerns by noting that users “only have to submit verification to the covered website itself or the third-party service with which the website contracts,” and that “both those entities have every incentive to assure users of their privacy.”

This reasoning troubled the dissenting justices. As Justice Kagan wrote, age verification “is turning over information about yourself and your viewing habits—respecting speech many find repulsive—to a website operator, and then to . . . who knows? The operator might sell the information; the operator might be hacked or subpoenaed.”

Eric Goldman, professor of Internet Law at Santa Clara University School of Law, echoed the dissent’s concern, writing that the Court “falsely equated age authentication of offline items like liquor sales, which raise no real speech issues, with restrictions on online speech." (Technology & Marketing Law Blog).

The Anonymity Question

The Court’s finding that adults have no First Amendment right to access age-restricted content “without first submitting proof of age” raises broader questions about online anonymity. While the Court limited this holding to content that is obscene to minors, the reasoning could potentially extend to other contexts where age verification is required, fundamentally changing how we experience the internet.

A famous 1993 New Yorker cartoon depicted two dogs at a computer, with one saying: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” Following this decision, that era of anonymous browsing may be coming to an end—at least in contexts where the government has determined that age verification serves an important interest in protecting children.

Industry Practices as Constitutional Evidence: A Problematic Precedent?

In a notable statement, the Court pointed to “the decades-long history of some pornographic websites requiring age verification” as evidence that such requirements don’t create “insurmountable obstacle[s] for users.” This reasoning raises important questions about how courts might evaluate future technology requirements, essentially using some large companies’ willingness and ability to implement expensive, complex systems as evidence that such requirements aren’t burdensome for all companies. This creates a problematic precedent for several reasons, including:

- Resource Disparities: Just because major corporations may be able afford sophisticated age verification systems doesn’t mean smaller platforms can do the same;

- Technical Complexity: Age verification is both technically challenging and expensive to implement correctly; and

- Compliance Costs: The Court’s reasoning could lead to dismissing legitimate concerns about compliance costs by pointing to successful implementation by well-resourced companies.

This may lead courts to underestimate the real barriers that new technology requirements create for smaller platforms and startups, potentially stifling innovation and competition in the online space.

Looking Ahead: What Questions Remain Open?

Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton settles some important questions while leaving many others unresolved.

Settled:

- States can require proof of age to access content that is obscene to minors;

- Age verification requirements to access content that is obscene to minors triggers intermediate scrutiny.; and

- The burden on adults to prove that they are adults—including verification methods that involve having to provide a government ID—should be viewed as “incidental.”

Still Open:

- Whether intermediate scrutiny is also the standard that should be applied to laws regulating non-obscene content, such as laws mandating age verification to access social media;

- How courts will balance child protection interests against privacy concerns in non-obscenity contexts;

- Whether the reasoning extends to broader platform design requirements beyond age verification; and

- How compliance costs and technical feasibility factor into constitutional analysis when evaluating smaller platforms.

Final Thoughts

This decision comes as the first major Supreme Court ruling on child online safety since the internet’s early days. Paxton signals the Court’s willingness to reconsider how First Amendment protections apply in the digital age, particularly when child safety is at stake.

For the many policymakers, platforms, and privacy advocates helping craft or involved in ongoing litigation over child online safety laws, this decision provides new constitutional terrain to navigate:

- For policymakers: The decision creates more room to craft child protection laws, but success will still depend on careful drafting that avoids excessive burdens on adult speech and access.

- For platforms: The ruling suggests that age verification requirements are here to stay and are likely to expand beyond adult content to other contexts involving children.

- For privacy advocates: The decision’s limited engagement with privacy concerns leaves important questions about data protection and surveillance unaddressed—issues likely to become more pressing as age verification requirements expand.

As courts across the country reconsider previously blocked child safety laws in light of Paxton, the coming months will reveal just how transformative this decision proves to be for the landscape of child online protection.

Footnote:

*When challengers argued that Texas’s law was not tailored appropriately “because it does not require age verification on other sites, such as…social-media websites, where children are likely to find sexually explicit content,” the Court explained that “under intermediate scrutiny, ‘the First Amendment imposes no freestanding underinclusiveness limitation,’ and Texas ‘need not address all aspects of a problem in one fell swoop.’” The Court went on to say that “the statute does not contain any special exception for social-media sites,” but that social-media instead “fall[s] outside the statute to the extent that less than a third of their content is obscene to minors” and that “it is reasonable for Texas to conclude that a website with a higher proportion of sexual content are more inappropriate for children to visit than those with a lower proportion.”