Policymaking on Education Data Privacy: Lessons Learned

April 2016

Amelia Vance

Republished courtesy of the National Association of State Boards of Education©

Introduction

When teachers and schools use data and technology to tailor instruction to individual needs, students benefi t through enriched, accelerated learning. Teachers and schools can use education data to measure whether particular teaching methods are promoting student learning. State policymakers can use data to make judgments about the eff ectiveness of standards implementation and then improve policies or allocate additional state funds or technology support in response. Parents can have timely information about whether their child is on track to graduate ready for college or a career and how their school compares with others in the state.

Protecting student data privacy is at the core of eff ective data use. Unfortunately, the data that schools use to improve instruction are not always adequately protected, and they are oft en disconnected, decentralized, or aggregated in a way that leaves the information vulnerable to attack. Th is vulnerability sparked a growing pushback against the use of data in schools.

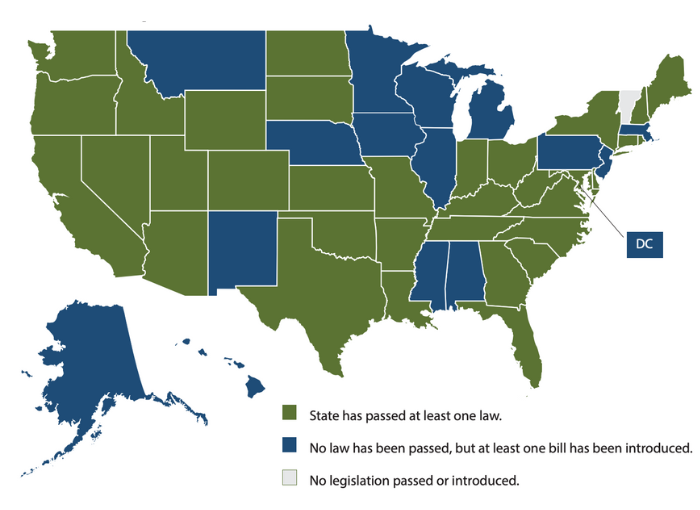

In 2015, 187 bills in 48 states were introduced on the topic, up from 110 in 2014. Since 2013, 34 states have passed new laws on student data privacy; an even larger number of states created new policies or regulations on this topic (see map 1). While states have clearly recognized the urgent need to act, many of the bills and policies unintentionally restrict educational technology use and innovation

Map 1: 34 States Have Passed 53 Laws Since 2013

State boards of education (SBEs) are major players on education data privacy: In 36 states, the state board has at least some authority over education data privacy, and states continue to consider expanding those powers. In doing so, many state legislators recognized that SBEs are well placed to protect student privacy. Boards can work directly with parents and educators by holding public hearings and creating committees, and they can respond quickly to changing technologies by developing regulations, guidance, and best practices.

Just as education data privacy was emerging as a hot topic in 2013, state boards sought assistance in understanding the issue. In mid-2014, the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE) launched a major eff ort to help SBE members address issues around data privacy. NASBE’s goal has been to ensure that state policies protect student privacy while enabling the critical improvements in education that come from the use of data to personalize learning and support equitable opportunities for all students.

Over the past two years, NASBE provided technical assistance to policymakers in 5 states, held education data privacy meetings attended by representatives from over 30 states, published analyses on student data privacy, participated on panels, and joined coalitions representing key parties working in the student data privacy space. In addition, I have spoken with nearly every state education agency on this topic and gathered every state law and regulation that deals with education data privacy, as well as many state policies and guidance, in order to prepare analyses, conduct policy audits, and identify gaps in a state’s education privacy landscape.

This work has yielded key lessons that should be shared with all policymakers interested in education data privacy. In particular, SBEs have been given many powers that—if exercised—could promote an essential balance between protection of privacy and effective use of data and technology in education. My hope is that the knowledge gained during this recent cycle of rapid and vigorous policymaking can be used to create the best possible education data privacy regime across the country.