Data Privacy Laws Follow Lead of Oklahoma and California

May 2016

Amelia Vance

Republished courtesy of the National Association of State Boards of Education©

Across the country, states have engaged in the sincerest form of flattery in passing student data privacy laws that echo provisions first laid down in two states.

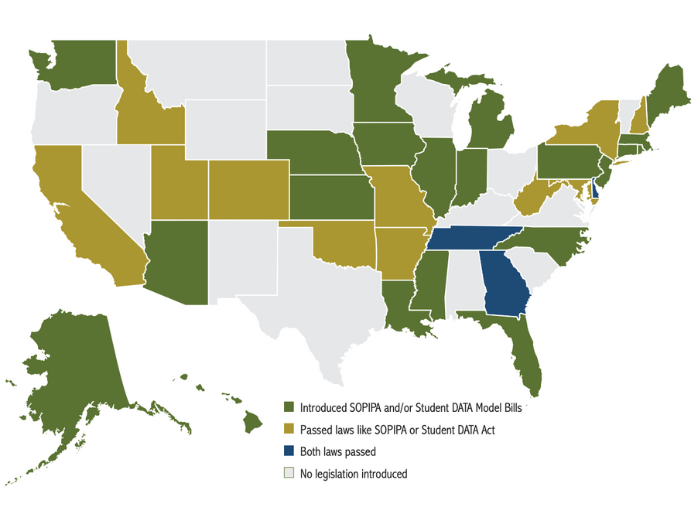

Since 2013, one or both of the student data privacy laws passed in Oklahoma and California have shaped bills that were introduced in 35 state legislatures and became law in 14 states. The Oklahoma law, passed in 2013, focuses on actions of staff at the school, district, and state levels. The California law, passed in 2014, regulates nongovernmental actors, such as education technology companies, which gain access to student data in the course of their work with schools.

Oklahoma’s Focus on Transparency

Oklahoma’s Student Data Accessibility, Transparency, and Accountability Act (known as the Student DATA Act) arose just as privacy concerns about student data were beginning to surface. According to Linnette Attai, founder of education technology compliance consultancy PlayWell LLC, “When this climate of data privacy first emerged in its current form, this was one of the key questions: How are states understanding what data they have?”

The law assigned extensive responsibility to the Oklahoma State Board of Education, requiring it to set policies and establish safeguards for state-collected student data. Before its passage, student data was handled “largely at the staff level within the department, outside of any public process or public scrutiny,” according to Oklahoma State Representative Jason Nelson, coauthor of the bill.1 One of the concerns that parents and privacy advocates most frequently voiced was the lack of transparency about how government was using and protecting student data. By giving this authority to the state board, Oklahoma enhanced the transparency of its student data privacy decisions and created a model for the country.

The Student DATA Act set in stone best practices that were echoed in bills introduced across the country. It required the state board to develop policies and procedures that complied with all relevant privacy laws; ensure that data are accessible only to the people who need it to do their jobs, like a child’s teacher; ensure vendor contracts include provisions that safeguard privacy and included penalties for noncompliance; and submit an annual student data privacy report to the governor and legislature. The law also restricted the state’s ability to collect unnecessary and especially sensitive data from districts, such as Social Security numbers and biometric information.

Oklahoma’s transparency requirements are especially praiseworthy; they emphasize the need for public disclosure of policies. “States have been using education data obviously for quite a while to improve the education services that they provide and support their students, but they haven’t always done a good job of communicating how they were using information and how they were governing it and protecting it,” said Rachel Anderson, senior associate of policy and advocacy at the Data Quality Campaign. “This model was really innovative in that it really gave the public a sense of what was going on and ways that they could help hold the state accountable for their data activities.”

Transparency is not only a best practice, it can be the only way to push back against inaccurate information about student privacy that parents may gather from other sources. Chip Slaven, counsel to the president and senior advocacy adviser for the Alliance for Excellent Education, said schools want to avoid parents hearing information only from “the talk radio show or from some Internet blog that’s not informed.” He added that schools should ensure parents “know where to go when they have questions and have some sense of comfort that there are efforts being made to protect their child’s information.”

The Oklahoma law struck a balance between protecting student data and allowing use of those data to help children. Perhaps the best example is a clause that allows the state board to create exemptions to the law when the board deems that an unforeseen consequence of the law’s provisions harms students. The clause proved prescient: In 2015, a regulation passed by the Oklahoma Department of Education to comply with the law unintentionally restricted release of some district high school graduation rates. The state board used the exemption clause to allow a one-time release of graduation rates while the state amends its regulation.

Over the past three years, 22 states introduced bills based on the Oklahoma model, 10 of which became law (see map).

Figure 1. 14 States Have Passed Bills Like California’s or Oklahoma’s

California Restricts Private Firms’ Access

Regulating government actions was important but not sufficient for privacy advocates, who were also uneasy about the increasing amount of student data held by private companies. A 2014 survey from Common Sense Media revealed that 90 percent of parents surveyed were concerned about “how private companies with noneducational interests are able to access and use students’ personal information.” Many of those parents indicated they wanted to make it illegal for companies to sell students’ private information to advertisers and ensure tighter security standards for student data held “in the cloud.”2

In response, California passed the Student Online Personal Information Protection Act (SOPIPA) in 2014. It was the first law to specifically regulate third parties, like education technology companies. “Privacy protections that apply directly to noneducational actors [such as SOPIPA] are a more effective way to address stakeholder fears about commercial actors than trying to do so indirectly by restricting how schools share student data,” said Elana Zeide, a privacy expert from the NYU Information Law Institute.

Even though federal law already prohibited companies from advertising to students, SOPIPA went further, requiring that third parties not sell student data or use student data to create a “profile” on students for a noneducational purpose. The law also required that vendors maintain adequate security and delete student information when requested by the school or district. In order to balance privacy and beneficial uses of technology, the law explicitly allowed third parties— as authorized by the school—to use student data for adaptive or personalized learning. For example, a math games company could create a profile of a student that track what the student had accomplished previously and adjust the game so the math questions are at the right level for that student.

If third parties violate the law, SOPIPA allows the California attorney general to bring a case against the company in court. “SOPIPA paved new ground,” said Zeide, who added, “The devil will be in the details of implementation.” For example, vendors can disclose sensitive information for research, provided there are privacy and security protections in place, but it is unclear what the law considers a legitimate research purpose.

Such research might be undertaken to improve a product, but it also could further understanding of “how education is working and how students are actually learning,” said Brendan Desetti, director of education policy for the Software and Information Industry Association. Most experts said there will be no regulations to clarify such aspects of SOPIPA, so it is very likely some definitions will be clarified by judges as vendors are brought to court for alleged violations.

Since 2014, 26 states have introduced SOPIPA-style bills, with seven of those bills becoming law (see map).

What's Next?

Forty-nine states have introduced student privacy bills since 2013, with 35 states passing at least one law. However, some of these laws may not fully protect privacy, and others’ strictures are accidentally inhibiting districts from, in one case, enrolling students in a state scholarship fund.

Recently, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) dipped its toes into the student privacy debate, introducing a model bill in nine states that could add privacy protections for students in schools that provide each of them a computer or tablet. However, some of the ACLU language may trigger accidental consequences. For example, a requirement that parents opt in every time the school uses new technology could inhibit technology use in the classroom altogether.

In any case, “the layer of protection it adds [to have every parent sign a form] is illusory,” said Neil Campbell, director of next generation for the Foundation for Excellence in Education. If teachers are responsible for figuring out which parents have signed off on which technologies, Campbell added, “you’re just destroying any potential benefit that may exist [from education technology], and teachers are going to have to go back and find worksheets for the students that can’t use the computer because they don’t have the proper permissions.” While schools need to ensure student data are protected, they need to then “be trusted with doing that so that the teacher can put their attention where it really needs to be: on managing the students’ learning,” he said.

Vague regulatory language can also obstruct beneficial uses of data. When considering passage of new state regulations or other guidance on student data privacy, clarity is key. Attai noted that, for all their groundbreaking provisions, both the Student DATA Act and SOPIPA also have potentially confusing language. For example, SOPIPA does not clearly define what is meant by targeted advertising, Attai said. “It’s a new term,” she said. “We’ve always referred to advertising as behaviorally targeted or contextually relevant, and those come with definitions that have been in place at the Federal Trade Commission level through reports, cases, and other legislation. It’s been very challenging for industry to understand what needs to be in place in order to be compliant with SOPIPA.”

Kobie Pruitt, education policy manager at the Future of Privacy Forum, said that he would encourage state policymakers to look closely at definitions that could be too broad. As an example, he cited a Florida law that banned biometrics, which caused problems for special education classes that routinely used video cameras and recordings to help students. If the student has a speech impairment, for example, “a voice recording could be used to help chart their progress and show the successes teachers are having with that student,” Pruitt said.

Neither the Student DATA Act nor SOPIPA incorporated language around training teachers and administrators. “It’s very important that we have training as a part of the requirements,” Pruitt said. "Because with all these new laws, if teachers don't know how to navigate the new landscape, I don't think the laws are going to be effective."

Slaven agreed. "Whenever I see a proposal that's around professional development to help teachers or to help any school official who has to deal with data and privacy ... that's a game changer," he said. He added that most teachers and administrators likely "don't know a quarter of what they need to know on this issue. So they end up either not worrying about it like they should, or they overcompensate and do too much."

States that desire a comprehensive and smart approach to privacy, like Georgia and Delaware, have taken the next logical step: passing both a SOPIPA and an Oklahoma-style law in order to maximally protect student privacy while allowing for education technology in the classroom.

This may not be the right approach for all states. Some states, like New Jersey, already had Oklahoma-style regulations for student data in place prior to 2013. But for others, this approach could provide a starting place for states seeking the best ways to balance privacy and innovation.

Experts urge policymakers to first look at what laws or regulations they already have and then to identify gaps: "The answer to solving a problem or issue that is already covered by existing legislation is often not more legislation," Attai said, "but enforcement of the legislation we do have."

Resources

1 Jason Nelson, "Oklahoma's New Student DATA Act Sets Guidelines, Protections," The Flashlight (blog), September 26, 2013, http://dataqualitycampaign.org/blog/2013/09/oklahomas-new-student-data-act-sets-guidelines-protections/.

2 Amy Wilson, "National Poll Reveals Deep Concern for How Students' Personal Information Is Collected, Used, and Shared," KidsAction blog (San Francisco: CommonSense Media, 2014), https://www.commonsensemedia.org/kids-action/blog/naitonal-poll-reveals-deep-concern-for-how-students-personal-information-is.