Mitigating Risks in Student Surveys: An Overview of PPRA

June 2024

Jessica Arciniega, Katherine Kalpos, and Amelia Vance

CC BY-NC 4.0

Following the switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was widespread public concern about student mental health as students faced social isolation and lost access to vital school-based services. These concerns intensified when the 2023 US Surgeon General advisory showed an alarming upward trend in mental health issues among high school students from 2009 to 2019, including a 40% increase in reports of persistent sadness or hopelessness, a 36% rise in those seriously contemplating suicide, and a 44% jump in students making suicide plans.

Schools have long-relied on surveys, including Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) or school climate surveys,1 as critical tools for detecting potential risks in students' mental and emotional well-being and identifying what interventions students may need. The importance and prevalence of these surveys has notably increased in recent years, making it crucial for educators and school administrators to understand the legal requirements around administering surveys that ask questions aimed at understanding students' mental health, their levels of anxiety, and their engagement in risky behaviors.

Despite their utility, the improper implementation of surveys can put students’ personal information at risk and erode trust between schools and the communities they serve. This is especially true when surveys ask questions on sensitive topics such as drug and alcohol use, sexual orientation, or home life. In some instances, students' responses to such questions have been mistakenly shared outside school environments due to legal misinterpretations, accidents, or poor privacy protections.

Given the delicate nature of collecting student data, it is imperative that rigorous privacy, transparency, and consent protocols be established and maintained when administering SEL surveys. These protections are already required by the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA), a federal law that is often overlooked and misinterpreted.

With school districts, researchers, and policymakers in mind, we have created this guide to PPRA. It includes an overview of the law, lessons learned, and best practices to be aware of when making decisions related to the implementation of surveys. All key stakeholders must be aware of PPRA and its stipulations in order to ensure legal compliance, foster community trust, and promote positive social and emotional experiences for students without putting them at risk of privacy violations.

Why Was PPRA Enacted?

Enacted in 1974 and last amended in 2002, PPRA was designed to mitigate the risks of collecting sensitive student information by creating privacy and parental engagement parameters. One motivation behind PPRA was to address growing concerns from parents of students who were given intrusive surveys at school without their parents’ knowledge. When PPRA was first introduced and debated, Senator Ervin introduced a statement from a parent coalition to the Congressional Record providing examples of such invasive survey questions, including:

- “Are you an important person to your family?”2

- “Are you one of the last to be chosen for games?”3

- “If it would be hard for [the student] to face the ‘cold, cruel world.’” and4

- List the full names of classmates who “Fool around in class instead of working.”5

It flagged these questions as an “invasion of psychological privacy” where students “of all ages are asked to…unwittingly lay bare their inner-most feelings to the data collector for whatever purpose he may wish to make use of them.”5 The statement expressed particular concern about when questions were extracting “self-incriminating information” that “provide an evaluation team with data to be entered into a permanent personality record classifying students as maladaptive, aggressive, anti-social, emotionally disturbed, and predelinquent.”7 Senator Buckley, one of PPRA’s original sponsors, highlighted a recent case where a survey was given to attempt to identify whether eighth graders were “potential drug abusers”8 and the information was inappropriately shared. He noted that such incidents were deeply upsetting because they illustrate a scenario where, “the potential for harm… outweighed any good that might accrue.”9

The 1974 Senate debates around PPRA recognized the benefits of administering surveys responsibly and emphasized the need to involve parents. Senators cited several benefits of engaging with parents, including Senator Buckley’s statement that parental consent, while potentially an inadequate safeguard, at least “informs the parents, to some extent, about what is being done with and to their children in schools, and it offers the best available protection against educational abuses that I can think of.”10 He continued, noting that parental consent “will encourage schools to improve these types of programs and to eliminate the potential for abuses beforehand, thereby tending to reduce the future occurrences of irate parents going to court because of shoddy and harmful programs in the schools.”11 While education has changed a great deal since PPRA was first introduced, the motivations for passing the law and the protections it created remain important even today.

As with most privacy laws, PPRA is a balancing act that aims to enable critical data collection to foster better outcomes for students in an ethical and privacy protective way. But this balance only exists when PPRA is properly interpreted and followed. Overly restrictive interpretations of PPRA could hinder gathering information that is critical in addressing students’ needs, while lax interpretations of PPRA could lead to schools and researchers violating the law and compromising the trust and privacy of students. The following discusses key provisions of PPRA along with possible changes that could improve its application in light of evolving technology and data uses in education.

When PPRA Applies

Eight Sensitive Topics

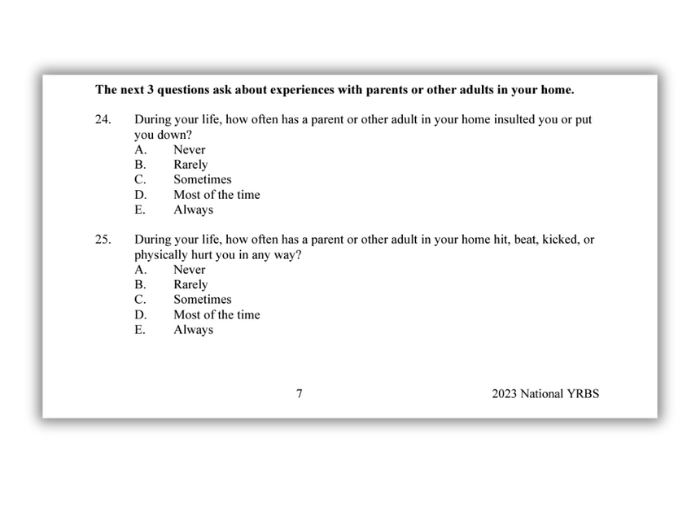

PPRA is designed to add protections for sensitive information including information that falls under any of the following topics outlined in PPRA:

- “political affiliations or beliefs of the student or the student’s parent;

- mental or psychological problems of the student or the student’s family;

- sex behavior or attitudes;

- illegal, anti-social, self-incriminating, or demeaning behavior;

- critical appraisals of other individuals with whom respondents have close family relationships;

- legally recognized privileged or analogous relationships, such as those of lawyers, physicians, and ministers;

- religious practices, affiliations, or beliefs of the student or student’s parent; or

- income (other than that required by law to determine eligibility for participation in a program or for receiving financial assistance under such program)”12

PPRA often applies to SEL and school climate surveys because they frequently include sensitive information about 1) “mental or psychological problems of the student or the student’s family” or 2) “illegal, anti-social, incriminating, or demeaning behavior [of the student].”13

Other Surveys or Evaluations

PPRA also includes protections for other surveys or evaluations, such as those that:

- Are required;

- Are created by a third party (regardless of whether the questions deal with the eight sensitive topics); and

- May elicit responses that fall under one of the eight sensitive topics (however, inferences are not covered).

This may seem straightforward, but survey questions may elicit sensitive information about the sensitive categories in ways the survey creators did not anticipate. Take for example a question asking “what do you like to do during recess?” While this may not seem like a question that would fall under PPRA’s eight sensitive topics, the student may respond that they spend recess alone in a corner of the playground. If this survey was given without providing parents notice and the opportunity to opt-in or out, the school would be in violation of PPRA because it elicited a response that could be considered to reveal anti-social behavior, which is one of PPRA’s eight sensitive topics.

PPRA may also apply in scenarios that are not intended to be surveys, such as when a researcher is evaluating an educational technology to determine whether it can improve students’ writing abilities. In this instance, the researcher may give students a generic writing prompt, such as “write about someone you look up to that has a positive influence in your life,” to obtain a baseline measurement of writing speed. For example, one student, Riley, writes about their past experience engaging in criminal behavior and how bonding with their minister has influenced them to stop committing crimes. Even though the researchers did not intend to administer a survey or collect sensitive information from students, Riley’s response may create unforeseen legal liability under PPRA.

Applying PPRA

Opt-In and Opt-Out

The rights that schools must provide to parents are determined by whether a survey covers protected categories and if it is required. At a minimum, schools must offer parents the right to opt-out of participation when the survey concerns protected categories. Affirmative, opt-in consent is only required when the survey covers protected categories, is part of a federally funded program, and student participation is required.

Table: Parental Opt-In and Opt-Out Rights Under PPRA14

| Student Participation Required | Covers Eight Protected Categories | Opt in/Opt out |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Provide notice and parents must opt in for the student to take the survey |

| Yes | No | Provide notice and parents have the right to opt out |

| No | Yes | Provide notice and parents have the right to opt out (but check your specific state law first) |

| No | No | Provide notice only if the survey was created by a third party. In that case, parents have the right to opt out. |

While the PPRA statute does not provide parents with the right to access their child’s answers to any survey questions, parents may still have access under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA); if a child’s answers are collected in an identifying form and the school retains those answers, the information would become part of the student’s FERPA protected education record to which parents have the right to access.

Parental Engagement

Under PPRA, schools are required to work “in consultation with parents” to develop local policies concerning student privacy, parents' access to information, and administration of certain physical examinations to minors.15 Schools must notify parents at least annually of these policies, as well as the dates the surveys are expected to be administered. This helps ensure that parents have a reasonable amount of time to consider the surveys, request review, and opt-in or opt-out of the surveys being administered to their child. The collaboration between schools and parents helps to fulfill one of PPRA’s goals: keeping parents involved in and informed of the education of their children. It also fosters trust and collaborative engagement from stakeholders and helps prevent survey questions and methodologies that may expose students to risk.

Anonymity

Anonymous surveys can be a useful tool for schools wanting to identify the needs of the larger school community without collecting sensitive responses directly linked to individual students. Anonymous surveys are not subject to PPRA’s requirements, however, such surveys may still be subject to PPRA requirements if responses could be traced back to individual students. Creating a truly anonymous survey is very difficult because even when schools take steps to anonymize responses, the risk of re-identification remains high. Advancements in technology and publicly available datasets can allow for previously anonymized survey data to be linked back to individual students with increasing levels of certainty, especially if there are unique combinations of responses. For example, seemingly unrelated data elements, even limited data elements such as just race and participation in afterschool activities, can potentially be connected to re-identify a student on the volleyball team who is also a member of the yearbook committee. Additionally, surveys that incorporate questions with open-text responses–as opposed to questions with a pre-selected list of responses to choose from–are particularly difficult to conduct anonymously because students are using their own words, potentially disclosing identifiable information (such as names, locations, or specific details about their experiences) and their unique speech patterns.

Lessons Learned

The process of applying PPRA can be complex, making it easy to violate PPRA without proper understanding and implementation of its requirements. Even surveys given with the best of intentions may violate students’ privacy and damage the relationships between schools and the communities they serve.

For example, several school districts in the Pacific Northwest administered questionnaires aimed at identifying and assisting young people facing challenges related to substance abuse, mental health, and other critical issues.16 The survey asked students to reveal personal information on a variety of sensitive topics—including substance choices, mental well-being, and emotional behavior. The districts generally characterized the survey as anonymous, and thus not subject to PPRA, so some districts did not inform parents before administering the survey. That being said, most districts still engaged in some form of parental engagement, as “Parents in most cases receive a general notification about the program with the option to opt out, but not detailed information about sensitive questions like gender and sexuality.”17 However, this often did not meet the level of parental engagement established under PPRA, as the districts would have needed to provide parents with a copy of the survey questions beforehand.

Characterizing the survey as anonymous led to a key question for the districts: if this survey is anonymous, would the data collected under the survey constitute part of a student's educational record? If it was part of the education record, parents would have the right to access this information under FERPA. If it was not, there is a risk that the data collected by this survey could be publicly disclosed, jeopardizing student privacy.

Five districts, incorrectly believing the survey responses were anonymous and thus not educational records protected under FERPA, shared the information “with limited or no redactions” with a journalist who requested the information under Washington’s Public Records Act.18 Such disclosures likely included information that could be connected back to individual students, as “Three districts [responding to the journalist’s public records request] provided anonymous student responses with many redactions, admitting that the data shared with King County and its contractors contains identifying student information.”19 (emphasis added). Even though student names were not attached to the survey responses, members of the school community could identify many of the responses, particularly where “students responded to open-ended questions with names of family members, friends and pets.”20 In hindsight, it is clear that the surveys were not anonymous and should have been subject to PPRA’s parental engagement requirements.

In another example, a district in the Northeast distributed a series of questionnaires that were meant to be anonymous, asking students about sensitive information such as gender identity and discrimination.21 Unfortunately, the school administration did not inform parents about the survey’s content beforehand, nor did they solicit parental consent. Parents were upset to learn that they had not been informed about the nature of the survey, nor given a sufficient opportunity to opt in or out before the survey was administered to their children. This led to an uproar within the school community, including yelling at a school board meeting and an alleged ethics complaint against the president of the school board.22

Additionally, some aggrieved parents brought the action to an administrative court, where the judge found that the questions in the questionnaire about gender identity and gender discrimination may elicit responses about sex behavior or attitudes,23 which is one of the eight sensitive categories protected under PPRA. As such, PPRA required the district to engage with parents before administering the survey to students. The judge ordered the district to discard the surveys and remove the results from the website, student records, and anywhere else the survey was distributed.24

These incidents highlight the paramount importance of building and maintaining trust between parents and school districts, particularly regarding the handling of sensitive student information. When trust is compromised due to the lack of communication or mishandling of such data, parents are more likely to advocate for stringent measures, including a complete ban on SEL surveys that could potentially benefit students by identifying their needs and offering support. This reaction, while understandable from a parental standpoint, inadvertently hampers the educational institution's capacity to provide crucial interventions and support systems for students. It is crucial for schools to adhere to legal frameworks like PPRA and FERPA, ensuring parental rights are respected and student privacy is safeguarded. Ultimately, the goal should be to foster an environment where educational tools and surveys can be utilized responsibly to benefit students, without eroding parental trust or compromising student privacy.

Best Practices

Given the complexities and ramifications of mismanaging sensitive student information, education authorities and school districts must exercise utmost caution and meticulous planning when collecting student data through surveys. To minimize potential missteps and uphold student privacy alongside parental trust, we recommend local education agencies implement the following measures:

- Educational Training: School staff, including administrators and teachers, should receive regular student privacy training that covers the nuances of PPRA. This would enable them to understand the role of this legislation and recognize when parents have a legal right to review and consent to surveys.

- Transparency and Engagement: Schools should strive for transparent and proactive engagement with parents about the intention, content, and confidentiality of surveys they intend to administer to students. Open forums, informational sessions, and detailed FAQs can demystify the survey process for parents, alleviate concerns, and foster a cooperative atmosphere. For example, a school hoping to administer a school climate survey to students can explain the purpose and importance of the survey to parents upfront, sharing an overview of what types of questions will be asked.

- Weigh Benefits and Risks: Before adopting or administering surveys, schools must weigh the benefit of the insights gained from such surveys against the potential negative legal, equitable, ethical, and privacy impacts for students. This process can help identify potential risks of collecting and running potentially harmful analyses on student responses, such as the previously-mentioned attempt to label eighth graders as potential drug abusers, and mitigate them before they become major issues. Schools should also regularly review their survey policies and procedures to ensure they are in line with current legal requirements.

- Notice and Consent: Schools must ensure that parents receive proper notice and the opportunity to consent to PPRA covered surveys. The school must provide details about the survey and its purpose in advance of survey administration, along with an option for parents to opt-in or out for their child.

- Additional Infrastructure for Identifiable Surveys: Before schools administer surveys allowing for the identification of individual students who may need additional support, the schools must ensure they have the capacity and resources necessary to provide the students identified as needing support with the help they need in a non-punitive manner. This may include adopting a robust response plan that is part of the school’s overarching support system for students.

- Prioritize Anonymity: Wherever possible, schools should strive to administer surveys anonymously to ensure that student data is protected, allowing schools to learn about trends affecting the school generally while protecting individual students' privacy. This can include restricting open-text questions where students may provide identifiable information.

- Data Governance: Schools should have clear policies about how survey data will be collected, used, retained, stored, shared, and destroyed. Often, there is no need to retain or share individual survey responses; these can be anonymized to preserve only the key insights while minimizing the risk of information breaches.

- Data Categorization: Establish clear protocols for categorizing identifiable survey responses as personally identifiable information (PII) protected by FERPA, including assessing whether the data has been adequately de-identified. Schools should also have guidelines for handling access requests for student data from parents or third parties.

- Data Security: Schools, counties, and any involved third parties must have a plan in place to protect the sensitive data collected from students through surveys. This should include using secure servers, implementing data encryption protocols, and establishing clear guidelines for data access.

Respecting and protecting student privacy is not just a legal obligation, but a foundational element of trust in the educational ecosystem. By adopting these best practices, school districts can better navigate the complexities of conducting SEL surveys, ensuring that they harness valuable insights for student support while firmly upholding the principles of privacy and parental consent.

Closing Thoughts

PPRA is an essential legislative framework that safeguards student privacy and upholds parental rights when surveys collecting sensitive data from students are administered at school.

While compliance with PPRA is a legal obligation for schools, its underlying principles extend far beyond mere adherence to legal requirements. This legislation, born out of a need to restore trust between schools and parents following incidents of invasive surveys administered without parental consent, emphasizes the paramount importance of transparency and protection in handling sensitive student data. The foundational principles of PPRA are crucial, especially for SEL surveys, which have taken on increased significance in identifying the emotional and psychological needs among students amid the ongoing youth mental health crisis.

However, the value of SEL surveys hinges on ensuring that past mistakes—where the lack of communication and transparency led to breaches of trust and the exposure of sensitive student information—are not repeated. PPRA serves as more than just a regulatory measure; it's a set of guidelines that promotes an informed and respectful approach to handling of student data, thus underpinning the broader objectives of SEL surveys to responsibly enhance student wellbeing. By adhering to PPRA, educational institutions can mitigate the potential harms resulting from improper data collection, thereby preserving the integrity of SEL surveys and their capacities to catalyze positive change. This adherence is not solely about complying with the law but about upholding a commitment to the underlying principles in order to strike a balance between gaining invaluable insights from these surveys and respecting the privacy and trust of students and their families. Navigating this delicate balance requires a steadfast dedication to the core principles of PPRA, ensuring that schools can continue to support their students' emotional and mental health needs without sacrificing trust and transparency.

In light of these considerations, it becomes increasingly important to enhance public awareness about PPRA and its provisions. Broad understanding among stakeholders and training is needed to fully realize the potential of PPRA to safeguard sensitive student information while promoting beneficial educational research.