Recapping USED’s Recent Surge in FERPA Enforcement Activities

April 17, 2025

Morgan Sexton and Amelia Vance

CC BY-NC 4.0

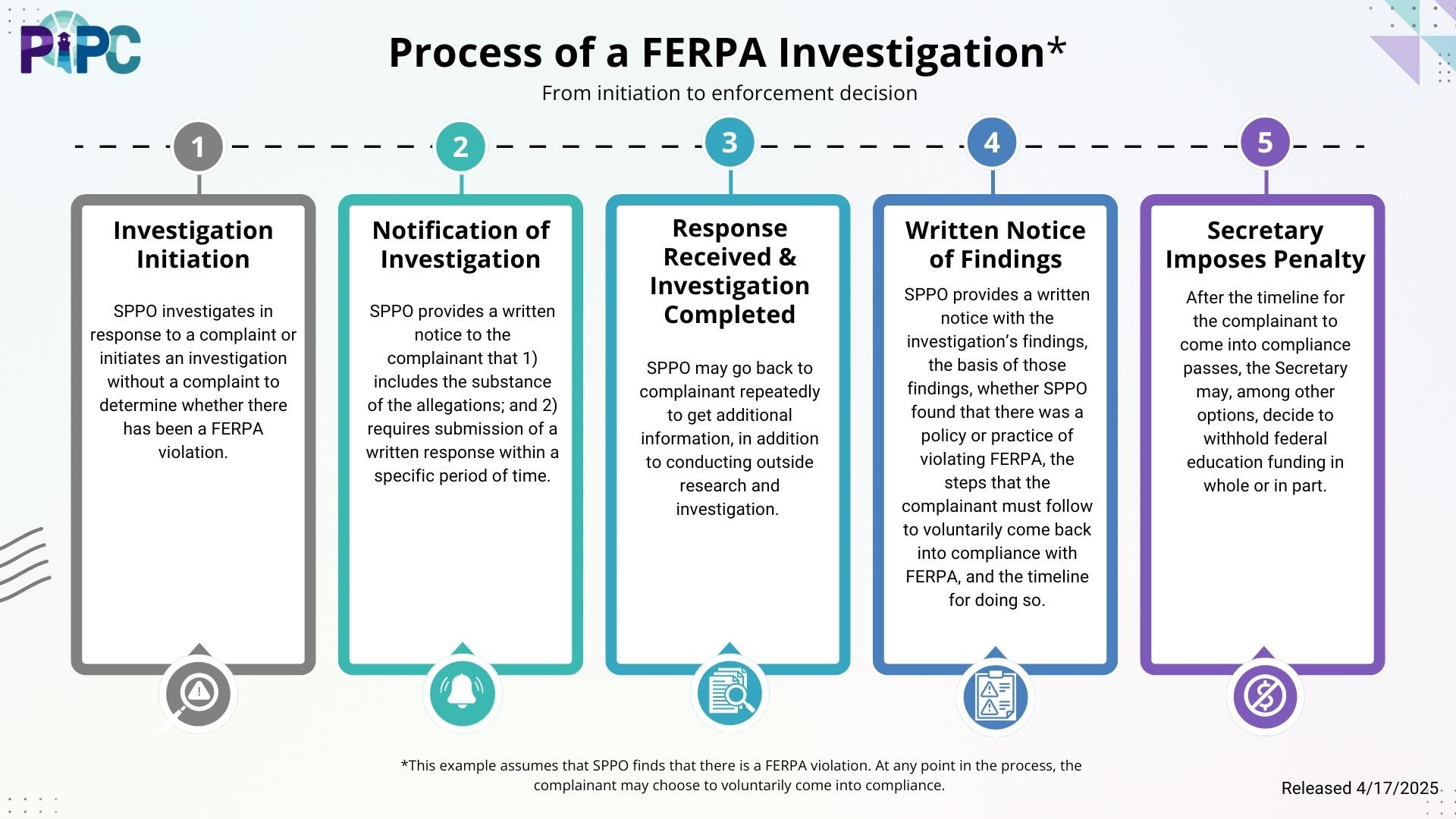

The student privacy landscape has shifted dramatically in recent weeks, with the U.S. Department of Education (USED) initiating two statewide FERPA investigations in California and Maine. This blog post unpacks these investigations and shares our new infographic showing the steps in a FERPA investigation.

As always, if you have any questions feel free to contact our team!

TLDR:

On March 27th and 28th, the USED Student Privacy Policy Office (SPPO) launched two FERPA investigations of the California and Maine state education agencies. The investigations primarily relate to parent rights to access education records related to the gender identity of their children.

- California: SPPO’s investigation into California centers on a recently passed law that SPPO says may “conflict with FERPA by prohibiting schools from requiring personnel to disclose a child’s ‘gender identity’ to that child’s parent.”

- Maine: SPPO’s investigation into Maine follows reports alleging that “at least 57 of its 192 school districts have policies that exclude parents from knowing whether their children start identifying as transgender.”

In both letters, it is unclear if any districts denied a parent access to their child’s education records in an effort to follow California’s law or the Maine districts’ policy.

Below we provide an overview of the FERPA enforcement process–including our new infographic illustrating how FERPA investigations work–and details about both investigations.

The Process of FERPA Enforcement

Schools–including SEAs or other types of LEAs–that have a “policy or practice” of violating FERPA may potentially lose federal funding. A single violation typically does not establish a “policy or practice” of violating FERPA. However, USED can find that a single violation of FERPA is enough to necessitate enforcement action when they determine that said violation is especially egregious.

But USED can only withhold federal funding under FERPA when an educational agency or institution has a “policy or practice” of violating FERPA and refuses to modify that policy or practice to come into compliance with FERPA. Federal funding can only be terminated under FERPA if “compliance cannot be secured by voluntary means.” (20 USC 1232g(f)).

Our infographic, below, shows the steps of the FERPA enforcement investigation process.

As far as we know, it is uncommon for USED to self-initiate investigations without receiving a complaint from parents or eligible students. It is also unusual for the department to initiate enforcement actions at the state–rather than local–level. However, USED’s FERPA enforcement process has historically been opaque (see more in our recommendation for fixing FERPA’s enforcement). Therefore, it is possible that there were similar investigations in the past that were never publicized.

California FERPA Investigation

The Announcement

On March 27th, USED announced that the Student Privacy Policy Office (SPPO) had launched an investigation into the California Department of Education (CDE) for alleged FERPA violations relating to the recently enacted California Assembly Bill 1955 (“AB 1955”). The department stated that “SPPO has reason to believe that numerous local educational agencies (LEAs) in California may be violating FERPA to socially transition children at school while hiding minors’ ‘gender identity’ from parents,” and that, “Given the number of LEAs that appear to be involved, SPPO is concerned that CDE played a role, either directly or indirectly, in the widespread adoption of these practices.”

The press release goes on to say that:

“California Assembly Bill 1955, which was signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom and took effect on January 1, 2025, appears to conflict with FERPA by prohibiting schools from requiring personnel to disclose a child’s ‘gender identity’ to that child’s parent. As a result, according to the California Justice Center, ‘every public school in California has a policy of denying, or effectively preventing, the parents of students...the right to inspect and review the education records of their children.’”

The Investigation Initiation Letter

SPPO’s investigation initiation letter to California cites the following legislative analysis for AB 1955:

“While parents/legal guardians have the right to review and amend their students’ educational records, courts have recognized that outing a minor to their parents or guardians can violate the minor’s constitutional right to privacy, even if the minor is out at school or socially (see Cal. Const., art. I, § 1; C.N. v. Wolf (C.D. Cal. 2005) 410 F.Supp.2d 894, 903; see also Sterling v. Borough v. Minersville (3d Cir. 2000) 232 F.3d 190, 196). By prohibiting school policies that require outing a student to their parents or legal guardians, regardless of the circumstances, this bill would reduce instances where teachers and administrators violate students’ right to privacy.” (emphasis added, California Senate Committee on Education, May 24, 2024 Bill Analysis for AB 1955, p. 7)

The investigation initiation letter also quotes the following analysis from the California Justice Center:

“AB 1955 purports to create a confidential relationship between a child and a school district, and a constitutional right to privacy in a child’s identity from that child’s parents— which does not exist in the state or federal constitution. AB 1955 classifies providing education records pertaining to a child’s gender dysphoria as ‘outing’ a child to the child’s parents. If a school is facilitating and accommodating a child’s name and gender change at school, however, those documents must be disclosed to a parent upon request under FERPA. Likewise, a child’s school work must be produced in response to a FERPA request, even if it discloses a child’s new ‘gender identity.’

AB 1955 purports to exempt records pertaining to a child’s gender identity from disclosure under FERPA absent consent of the student. FERPA provides no such exemption, and provides full rights to parents before a child turns 18.” (emphasis added)

Does AB 1955 conflict with FERPA?

As noted above, the SPPO letter cites the legislative analysis of AB 1955, not the final text of the law. So what does California’s law actually say about disclosing information about a student’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to parents without student consent?

School employees “shall not be required to disclose any information related to a pupil’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to any other person without the pupil’s consent unless otherwise required by state or federal law” (Section 5, emphasis added).

School districts are prohibited from “enact[ing] or enforc[ing] any policy, rule, or administrative regulation that would require an employee or a contractor to disclose any information related to a pupil’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to any other person without the pupil’s consent, unless otherwise required by state or federal law” (Section 6, emphasis added).

AB 1955 notes that these provisions do “not constitute a change in, but [are] declaratory of, existing law.”

The provisions quoted above likely don’t conflict with FERPA, since the law explicitly carves out situations where federal law requires disclosure; this would encompass FERPA requirements to allow parents to access their child’s education records.

Open Question: Were Any Education Records Actually Withheld From Parents?

USED’s announcement about the California investigation didn't provide specific instances of schools refusing to give parents student information they requested. This was surprising, as formal FERPA investigations usually follow a specific violation or a complaint from parents.

However, the documents USED released (the press release and the letter starting the investigation) quoted a letter from the California Justice Center. That letter included a memo mentioning a possible violation where a California school allegedly denied a mother her right to see her child's schoolwork for months. However, according to the memo, this denial was based on a different law (AB 1266). If accurate, this would likely violate the parent’s rights under FERPA.

California’s Response

On April 1st, the CDE posted a letter to superintendents and administrators to clarify the relationship between AB 1955 and FERPA, stating:

“AB 1955 does not mandate nondisclosure. AB 1955 prohibits LEAs from mandating that staff disclose a student’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to another person without student consent, unless otherwise required by state or federal law. AB 1955 does not prohibit LEA staff from sharing any information with parents. Based on the plain language of both laws, there is no conflict between AB 1955 and FERPA, which permits parental access to their student’s education records upon request.” (Facts to Consider Regarding FERPA and AB 1955)

On April 11th, CDE sent their formal reply to SPPO’s investigation initiation letter. In a website post, CDE noted that:

“Based on the plain text of both laws, there is no conflict between FERPA and AB 1955.

Specifically, there is no conflict between the provisions of AB 1955 and a parent’s right to inspect and review their children’s education records, as defined in 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(4), under FERPA.

In addition, AB 1955 includes language requiring compliance with state and federal laws.” (Further Update Regarding FERPA and AB 1955)

You can refer to this CDE webpage for more updates as the FERPA investigation progresses.

Maine FERPA Investigation

The Announcement

On March 28th, USED announced that the SPPO had initiated an investigation into the Maine Department of Education (MDE) related to alleged FERPA violations. The press release states:

“This investigation comes amid reports that dozens of Maine school districts are violating or misusing FERPA by maintaining policies that infringe on parents’ rights. The districts’ policies allegedly allow for schools to create ‘gender plans’ supporting a student’s ‘transgender identity’ and then claim those plans are not education records under FERPA and therefore not available to parents.”

The Investigation Initiation Letter

As seen in California, the department is investigating these matters at the state level due to the amount of schools in Maine that allegedly have policies or practices that violate FERPA. As we mentioned above, the imposition of FERPA penalties (such as withholding federal education funding) is contingent on schools–including SEAs or other types of LEAs–having a “policy or practice” of violating FERPA, not just a single violation.

SPPO’s investigation initiation letter to Maine flagged that “numerous local educational agencies (LEAs) in Maine may be implementing policies and practices that violate the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA),” (emphasis added) and noted that “Given the number of LEAs potentially involved and to better inform our determination, SPPO is initiating an investigation to ascertain if the Maine Department of Education (MDOE) played a role, either directly or indirectly, in the LEAs’ adoption of these practices.”

The Policies

As with the California investigation letter, SPPO’s letter did not point to concrete examples of times that schools allegedly withheld records from parents. The USED press release about the letter, however, referenced a broader allegation not explicitly made in the letter, specifically that “districts’ policies allegedly allow for schools to create ‘gender plans’ supporting a student’s ‘transgender identity’ and then claim those plans are not education records under FERPA and therefore not available to parents.”

The Federalist article cited in SPPO’s letter referred to documents “obtained by Parents Defending Education through public records requests” allegedly showing that “at least 57 of [Maine’s] 192 school districts have policies that exclude parents from knowing whether their children start identifying as transgender.” The Parents Defending Education website had multiple blogs with downloadable policies and other documentation from Maine districts. In our initial review of those policies, we did not see any provisions explicitly violating FERPA; however, we did find several provisions that might lead to staff confusion about FERPA’s coverage and/or application (such as provisions differentiating what can be put in “permanent records” and “school records or other documents,” for example).

SPPO’s investigation initiation letter focused on two areas where Maine policies may conflict with FERPA:

First, SPPO references a Memorandum on the “Interpretation of the Education Provisions of the MHRA” that reads:

“In the event that the student and their parent/legal guardian do not agree with regard to the student’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression, the educational institution should, whenever possible, abide by the wishes of the student with regard their gender identity and expression while at school.” (PDF Page 4, emphasis added)

However, this excerpted provision doesn’t appear to implicate the treatment of PII in education records. Instead, it appears to relate solely to how students will be treated while at school. For this reason, the above language does not appear to implicate FERPA.

Regardless, SPPO’s letter does acknowledge that, “the inclusion of ‘whenever possible’ may infer some deference for other factors that could include federal laws such as FERPA,” but flags that “the overall memorandum on its face appears to give school officials discretion that would infringe on the rights of a parent under FERPA” (PDF Page 3). We agree with SPPO that the term “whenever possible” includes deference to potentially conflicting legal obligations, such as those that schools have under FERPA.

As we were reading the rest of the memorandum, we noticed that it included an odd reference to changing student names and/or pronouns in students’ “official records” versus “all other documents.” As mentioned above, this kind of differentiation of record types could be confusing to school staff about when names and pronouns are part of the “education record” that must be disclosed to parents under FERPA. However, it still does not directly conflict with FERPA.

Second, the letter flags the following provision in Maine law:

“A school counselor or school social worker may not be required, except as provided by this section, to divulge or release information gathered during a counseling relation with a client or with the parent, guardian or a person or agency having legal custody of a minor client. A counseling relation and the information resulting from it shall be kept confidential consistent with the professional obligations of the counselor or social worker.” (Title 20-A, Section 4008(2))

FERPA protects PII in education records. There is sometimes a misunderstanding about whether medical records fall under FERPA; however, FERPA will usually apply to any treatment or medical records of K-12 students. There is a FERPA exemption for certain “treatment records” for students over 18 or attending college, but that exception does not extend to K-12 (34 CFR 99.3 “Education records”; see our FERPA Exemptions table for more information). Unless the records of school counselors or social workers fall within a different FERPA exemption–such as the “sole possession” exception described below–FERPA would require schools to give these records to parents.

However, FERPA does have an exception for “records that are kept in the sole possession of the maker,” so long as those records are “used only as a personal memory aid” and not accessible to anyone else, except a “temporary substitute for the maker of the record.” Since school counselors and social workers may vary in how they keep and share their records of conversations with students, keeping those records confidential is not an automatic violation of FERPA. However, if the school counselor or social worker entered a record of their conversations with students into, for example, software that is accessible by someone else at the district, the records would be subject to FERPA and must be disclosed upon request.

Maine’s Response

We have not yet seen a response from MDE regarding this FERPA investigation. We will be keeping an eye out for future updates.

What’s Next?

This certainly won’t be the last time we’ll see FERPA in the headlines; given the press releases posted when the investigation was initiated, it’s likely we’ll hear about the next steps of the investigation from USED soon.