Lesson 6: Student Data Privacy Legislation Can Easily Cause Unintended Consequences, so States Should Take Caution and Provide Guidance to Clarify Laws or Regulations

Analyzing the effects of laws and policies in other states can help policymakers craft good data protection plans in their own. Other states’ laws sometimes off er cautionary tales of language that proves to be imprecise or implementation issues that were not fully thought through. Frequently, these issues arise when key stakeholders do not get a chance to weigh in on the legislation’s potential impact before its drafting.

Words Matter

Legislation on any topic should be carefully drafted and easy to understand, and this principle holds especially true in a complex, fast-moving arena like data and privacy. In 2014, several states introduced bills that would have rendered most school activities impossible because they placed severe restrictions on what data could be collected and how they could be used, even for education purposes. In a few states, these bills passed into laws that will create headaches for courts trying to interpret them and policymakers trying to implement them or introduce new technology-based educational innovations in a way that complies with them. Legislators did not mean to create these problems. But when laws contain ambiguous language or there is confusion about the meaning of provisions, policy will be enacted inconsistently.

In the drafting of legislation or a privacy policy, the specific words used, or not used, make a big difference. For example, the term personally identifiable information means different things in different contexts, and implementing a law that references it will be difficult if it is not defined clearly.

The vagueness of the New Hampshire law “generated questions for school districts across the state regarding how many public hearings and permission slips are needed for each recording, as well as how school officials should handle situations involving students with disabilities who regularly record classes.”23 The law’s sponsor has now written a clarifying amendment that may be passed in 2016, but in the meantime, New Hampshire districts and teachers seeking credentials they need to keep teaching are in chaos.24

Laws like these can hamper many great uses of technology in the classroom: teachers’ use of Skype to connect their students with children in classrooms around the world, for example, and telepresence robots that allow children who cannot attend school to be remotely present. In one Maryland school, this type of robot allows 10-year-old Peyton, undergoing chemotherapy for liver cancer in New York, to attend classes with her friends. Use of this technology would not be possible if Maryland or other states that support sick children in this manner had similar restrictions on video recording.

Neither is federal legislation immune to the problem of unintended consequences. A bill that Representatives Kline, Scott, Rokita, and Fudge introduced before the US House of Representatives in 2015 allows for student data to be shared with education researchers so educational agencies can determine, for example, whether students are learning what they need to know in high school in order to succeed in college. However, the provision states that research cannot be conducted, even if the school needs it, if it is not designed to improve the instruction or testing of students attending that school. This approach could restrict studies, for example, that deal with teachers only, or studies where a group of students who are not using a particular method are a control group in a research study. The language would also prevent the use of valuable past data to support future improvements to teaching and learning.

Privacy Problems with Privacy Legislation

In 2014, Senators Ed Markey (D-MA) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) introduced a bill in the US Senate that would have amended FERPA. The bill clarified the right of parents to access and amend their children’s education records, whether they are held by an educational agency or an outside contractor. To facilitate that access, the bill stated that school districts must maintain a record of all outside parties that receive student information and describe the information shared with them, which FERPA already required (though not as explicitly). The bill language explained that parents must be given access to personally identifiable information about their children that is held by an outside party to the same extent and in the same manner as the state education agency.25 At a minimum, this provision would have meant that each company needed to create files on individual students (although student data may have previously been collected only in the aggregate). The bill would also have forced companies to collect personal information about parents so the company could verify the identity of anyone asking for an individual child’s data. As the Data Quality Campaign noted after the bill was introduced, it makes more sense to ensure that schools, not companies, are keeping track of the information they share with companies so that parents can obtain files on their children directly from the school.26 Clearly, these consequences would have been contrary to the intent of the bill’s authors.

Another bill, introduced in Congress by Senator David Vitter (R-LA) in 2015, placed parental consent at the heart of its student data privacy framework. The bill would require parental consent for any third-party access to student data. However, a requirement that parents opt in every time a classroom uses a new technology or each time their child’s data are shared prevents schools from using data in positive ways. The requirement in the Vitter bill could mean that parents would need permission slips every time their child’s school adds new education soft ware or each time a new bus driver needs a child’s address. According to many privacy experts, parental consent can be appropriate in some circumstances, but not when it comes to core academic activities. The bill gives the illusion of transparency but would likely overwhelm parents with permission slips and make timely and effective implementation impossible. Schools may be left having to keep some student records on paper and other on computer systems, increasing the likelihood that they will simply lose track of some students.

A better approach is to give parents a role in protecting their children’s data while letting schools use valuable technology to help kids succeed. For example, Senators Blumenthal and Daines introduced a 2015 bill that allows schools to grant consent on parents’ behalf as long as they do so in compliance with FERPA— for example, by mandating that schools must share all of the data collected about a student with their parents upon request.

Privacy is important, and states and the federal government can protect it without inadvertently banning the use of data and technologies that aid children and prepare them to compete in the global economy.

The Need for Input

Many state bills introduced over the past two years did not give district stakeholders—from classroom teachers to chief technology officers to superintendents—an opportunity to weigh in on how the bills would affect educational work. This oversight created problems in a few states (see box 5). Louisiana districts, unsure of the implications of the student data privacy law the legislature passed in 2014, took an extremely conservative view about what information could be released: School administrators worried about showing football players’ names on the big screen during games, having a yearbook, and even whether they could hang student artwork in the hallways.28

[BOX 5]

Kansas Sees Unintended Consequence

When Kansas lawmakers passed a student privacy law in 2014, district stakeholders were not consulted. The law required schools to get parental permission before students could be surveyed on certain sensitive topics, and it did not provide an exception for surveys in which respondents were anonymous. Kansas conducts an annual survey in which students anonymously respond to questions about risky behaviors such as drug or alcohol use. The survey helps nonprofits and districts target support to schools with high incidences of reported risky behavior. As a result, districts projected that parents would not return sufficient numbers of permission slips and that the number of children taking the survey in 2015 would drop to 25,000, compared with 100,000 who took the survey in 2014.

Source: Mike Hendricks, “Unintended Consequences Cripple Kansas School Surveys of Student Use of Drugs, Alcohol,” Kansas City Star, January 6, 2015.

The law was amended in 2015 to give districts more discretion. However, districts had already spent countless hours complying with the law, going as far as sending teachers on home visits to get permission forms signed.29 If legislators had met with district staff before the law’s passage in 2014, this unintended consequence could have been avoided.

Biometric data are commonly used as an authentication mechanism in which a physical characteristic is measured or compared against stored information—for example, scanning a fingerprint or using facial recognition. However, some have defined it more broadly to incorporate any stored data on physical characteristics that might be used in school, such as T-shirt sizes. Several state laws passed in 2014 and 2015 restricted biometric information collection but didn’t define the term.

States should identify who needs to be at the table as they prepare to make decisions about privacy laws and policies. Parent voices are an essential part of this process, but so are teachers, principals, administrators, chief technology officers, vendors, lawyers, and state leaders. All can help ensure that policies are comprehensive and have wide support across the state.

Another problematic provision of the Kline, Scott, Rokita, and Fudge bill deals with the security safeguards, and it also illustrates the importance of running legislative language past schools, districts, and other stakeholders. Security safeguards are essential: Schools and service providers must establish them to prevent malicious actors from gaining unauthorized access or disclosures. Without those safeguards, even the strongest privacy protections could be for naught. The Kline bill, however, gave schools and local and state education agencies the responsibility for ensuring that the third parties with which they contract have adequate information security practices. This presents an insurmountable burden for almost all schools, since they simply do not have the expertise or resources to assess third parties’ practices or determine whether they are complying with industry security standards. Requiring schools rather than third parties to fulfill this requirement thus virtually guarantees noncompliance. If schools and districts had been consulted, the bill might instead have given vendors responsibility for legally certifying that their security meets industry standards or included another provision to take the burden off schools or districts, which lack the expertise to certify security.

Asking those who have to implement laws how they would affect their districts or schools is one of the best ways to avoid such accidents in Congress and state houses. Unless such consultations take place, new student privacy laws will likely end up harming students more than they protect them.

Policymakers should also discuss potential laws or rules with people working in industry. Protections that seem reasonable to laypeople may strike someone with technical expertise as unimplementable. Data privacy inherently involves technology, so it is vital to have someone familiar with technology—and in the myriad forms likely to exist across districts—providing input on all decisions. Such input could waylay, for example, a law that one state considered to require that data “in the cloud” be segregated by school—technologically impractical and cost prohibitive.

Industry may also be able to help keep laws within their intended confines. For example, such input could have prevented the case in which a Louisiana parish decided to forgo creating a yearbook because staff believed a 2014 state law required written consent of each parent in order to include each child in the yearbook.

Many states have decided to require “comprehensive security” for all vendors, with no differentiation between those that handle sensitive information such as health records and those whose soft ware contains aggregated “here’s how well this student played this game” information, which wouldn’t need a similarly high level of security. Some state and district contracts ban the use of a “portable media device” to store or transmit student personally identifiable information. But since a camera is technically a portable media device and pictures are ”personally identifiable,” such a ban could encompass things like school pictures or at a minimum require that a school or district revise policies to clarify that taking school pictures is acceptable.

Obviously, state legislators do not intend to ban school pictures or restrict student access to technologies that could help them learn better or teacher access to software that helps identify students who need extra help. By inviting companies to the table, states can avoid accidentally doing these things.

Fear-Based Policies

Fear drives some bills’ drafting but typically fails to produce the best legislation. Such laws will likely need fixing down the road. The Vitter bill, for example, forbids funds from being spent to collect data measuring “any type of psychological parameter” and then fails to define “psychological parameters,” opening the door for uneven, confused, and retrogressive interpretations. Left undefined, this aspect of the legislation could be understood to ban almost all tests or quizzes because they score student knowledge—a psychological parameter. Though the provisions of this bill on psychological data collection reflect real stakeholder concerns, the ban is so widely targeted and loosely written that it would likely cause more confusion and harm than good.

The bill could also ban college and career counseling given to students by forbidding “any effort to obligate an elementary school or secondary school student to involuntarily select a career, career interest, employment goals, or related job training.” Many students rely upon their counselors’ input to not only suggest possible college and career options but also to help guide them through complex applications processes for postsecondary education and employment opportunities. Whatever modest privacy gains might be made if the bill became law are bound to be outweighed by the losses in student college and career readiness that would follow.

Finally, the bill stipulates that education records be destroyed any time a student leaves any educational institution. These conditions are simply too broad: Records would be automatically destroyed for transfer students and even students moving between schooling levels, impairing the continuity of learning during transition periods. This provision could be especially harmful for transient families, such as the children of parents in the military. The data deletion requirements would also harm students forced to leave their education system because of extenuating circumstances. If these students were to attempt to finish their education, they would return to find their records had been destroyed.

It is vital to strike a balance between privacy and effective use of student data and education technology. Most states have passed laws that create real solutions, rather than reactionary rules guided by fear. For example, many states have created a governance structure for schools, districts, and states, or they directly regulate companies’ actions. State policymakers should steer clear of legislating fear-based policies.

Lesson Learned

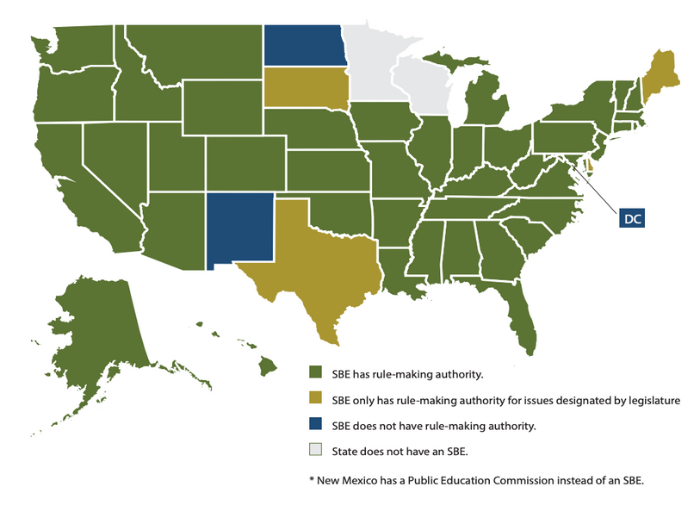

It is essential for all data privacy legislation to be vetted with a fine-toothed comb for vague language that may unnecessarily restrict the positive use of data. SBEs are ideally placed to fix these problems: 45 have rule-making authority, and many have received additional authority from recent state student privacy laws. Consequently, some state boards can pass binding rules, which essentially work just like law. Such rules can spell out guidance on problematic student data privacy laws. While state legislatures need to act to fully fix a law that has produced many unintended consequences, the state board can mitigate those consequences in the short run and give clarifying guidance to state education agencies, districts, and schools guidance (see map 2).

State boards can also call for proper review of legislation to forestall unintended consequences as legislation is being considered, using their platform as public officials. They also can convene stakeholders to ensure their voices are included in the law- and rule-making process.

Map 2: SBE Rule-Making Authority

Lesson 7: Human Error Is the Biggest Factor in Privacy Violations, so Training Is Essential

According to IBM’s 2014 Cyber Security Intelligence Index, human error is a factor in 95 percent of all data security incidents.31 Many are avoidable mistakes that could be minimized with training and oversight. All staff should be made aware of the importance of creating passwords that are not easy to guess, double-checking emails when sending attachments to ensure that the right data are sent, detecting whether an email has a potentially malicious link, and knowing what to do if a device with sensitive information is lost.

Such training can prevent major data breaches, such as the one that occurred in Chicago in 2013, which resulted in the names, birthdates, gender, ID numbers, and exam information of 2,000 students being accidentally posted online.32 NASBE’s 2014 Public Education Position on student data privacy recognized this need. It noted the importance of states creating a plan to ensure “educators and administrators have the knowledge, skills, and support to use education data effectively and securely.”

Anyone who handles data should know how to protect those data. They also need a thorough understanding of how to use data—and how not to. Bill Fitzgerald, privacy initiative director at Common Sense Media, cited a privacy violation that exemplifies the need for such training: A school principal posted a question about a student-related issue on a vendor’s website, disclosing the student’s first and last name in order to elicit information from the vendor. Worse, the vendor replied on a publicly accessible webpage. The principal and the vendor’s staff would have benefi ted from training on privacy laws and thus would have learned “the implications of sharing student information, including information about behavioral issues, on the open web,” Fitzgerald said.33

All district and school staff need such training. Most people press “yes” when they download an app to their tablets without reading the terms of service. However, when teachers are downloading that app to students’ tablets, they must know what information that app is collecting and how that information will be used, stored, and shared. Teachers can learn to recognize potential privacy hazards and when they need to talk to an administrator to see if a particular app is safe to use. Districts should also decide what level of authority teachers have to make these agreements on behalf of the schools and ensure teachers are aware of the policies.

Although more than 300 bills have been introduced over the past two years on student data privacy, few mention training. Paige Kowalski, vice president of policy and advocacy at the Data Quality Campaign, noted that it will be difficult for districts and educators to implement new state laws with fidelity without training, especially considering the large number of new roles and responsibilities districts are expected to take on under those laws.34

Despite the lack of a training requirement in state laws, many states are nonetheless beginning to take action. Maryland and Virginia have policies requiring comprehensive privacy training for education personnel. Similarly, Colorado requires new SEA employees to participate in an annual information security and privacy fundamentals training in order to retain access to the department’s network.35 Wisconsin’s public training module off ers a lesson followed by a quiz on student data privacy on the SEA’s website.36 Some school districts, such as the Cupertino Union school system in California, offer a preapproved list of websites, apps, and other tools that teachers access in coordination with data privacy training.37 West Virginia’s SEA will review vendor contracts with districts to help ensure that the contract’s privacy and security safeguards are adequate.

Regardless of the approach, training is essential. The Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (PRC) tracks data breaches across the United States. As of February 23, 2016, the PRC Chronology of Data Breaches documented 767 breaches that involved educational institutions and were made public between 2005 and 2016. These incidents involved nearly 15 million breached records.38 Of those breaches, 221 occurred because someone accidentally posted sensitive information on a website, mishandled information, or sent sensitive information to the wrong party. Those 221 do not include the multiple breaches that occurred due to other types of human error: a teacher not locking their computer at lunch, an administrator clicking on spyware or malware, or a flash drive falling out of someone’s pocket at a restaurant.

Lesson Learned

Policymakers must ensure that each state has training laws and policies and identify resources to make training feasible. Especially in the states where state boards have rule-making authority, they can set training policies themselves or can mandate or recommend that each district create an education data privacy training plan. Many state boards also have authority over teacher preparation standards and administrator training and can require or strongly suggest that administrator and teacher preparation colleges cover this topic. “Even though the odds of an earthquake are low, teachers in California are trained how to keep students safe.” said Kowalski, “Why do we continue to risk student safety by not also training teachers how to deal with the far more regular occurrences of privacy and confidentiality breaches?”

Resources

1. R.R.S. Neb. § 79-2,104.

2. W. Va. Code § 18B-1D-10.

3. N.J. Stat. § 18A:36-19.

4. Jason Nelson, “Oklahoma’s New Student DATA Act Sets Guidelines, Protections,” The Flashlight (blog), September 26, 2013, http://dataqualitycampaign.org/blog/2013/09/oklahomas-new-student-data-act-setsguidelines-protections/.

5. Nate Robson, “State Education Board Votes to Allow Data Release,” Oklahoma Watch, Aug. 31, 2015, http://oklahomawatch.org/2015/08/31/state-education-board-votes-to-allow-datarelease/.

6. David Leonhardt, “A Case Study in Lifting College Attendance,” The New York Times, June 10, 2014.

7. Aimee Rogstad Guidera, “Teachers and Parents Need to Support Their Kids’ Learning,” Huff Post Education (blog), April 29, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/aimee-rogstadguidera/teachers-and-parents-need_b_6771608. html.

8. Troy Wheeler, “Th e Impact of Student Data (or Lack Thereof): A Parent’s Perspective on the Power It Holds,” Ed-Fi Alliance (blog), June 12, 2004, http://www.ed-fi.org/blog/2014/06/impactstudent-data-lack-thereof-parents-perspectivepower-holds/.

9. Tim Henderson, “Americans Are on the Move—Again,” The Pew Charitable Trusts (blog), June 25, 2015, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/ stateline/2015/6/25/americans-are-on-the-moveagain.

10. Jose Ferreira, “The Mathematics of Effectiveness,” Knewton (blog), April 17, 2014, https://www.knewton.com/resources/blog/ceojose-ferreira/big-data-mathematics/.

11. Stephen Balkam, “Learning the Lessons of the inBloom Failure,” The Huffington Post (blog), April 24, 2014, http://www. huffingtonpost.com/stephen-balkam/learningthe-lessons-of-t_b_5208724.html.

12. “National Poll Commissioned by Common Sense Media Reveals Deep Concern for How Students’ Personal Information Is Collected, Used, and Shared,” Common Sense Media, January 22, 2014, https://www.commonsensemedia.org/about-us/news/ press-releases/national-poll-commissioned-bycommon-sense-media-reveals-deep-concern.

13. Joseph Jerome and Jules Polonetsky, “Student Data: Trust, Transparency and the Role of Consent,” Future of Privacy Forum, October 2014, https://fpf.org/wp-content/uploads/FPF_Education_Consent_StudentData_ Oct2014.pdf.

14. Aimee Rogstad Guidera, “Privacy and Trust: The Keys to Effective Data Use,” The Huffington Post (blog), January 28, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/aimee-rogstad-guidera/ privacy-and-trust_b_4673864.html.

15. Student Data Accessibility, Transparency and Accountability Act of 2013, OK. ENR. H.B. No. 1989 (passed May 29, 2013).

16. Olga Garcia-Kaplan, e-mail message to NASBE, March 2, 2016.

17. Amelia Vance, “West Virginia’s Steady Course on Student Data,” presentation, SXSWedu, Austin, TX, March 9-12, 2015.

18. Aspen Institute, Task Force on Learning and the Internet, “Learner at the Center of a Networked World,” (2014), http://www. aspeninstitute.org/sites/default/fi les/content/docs/pubs/Learner-at-the-Center-of-aNetworked-World.pdf.

19. Ok. Stat. 70 § 3-168.

20. Ca. Code 22.2 § 22584-22585.

21. De. Code 14 § 4111.

22. An Act Concerning Education – Student Data Privacy Council, MD. H.B. 430 (2016).

23. Paul Feely, “New Hampshire Schools Review Policy on Video Cameras in Classrooms,” The New Hampshire Union Leader, December 14, 2015, http://www.centerdigitaled.com/k-12/NewHampshire-Schools-Review-Policy-on-VideoCameras-in-Classrooms.html.

24. “Student Data Privacy,” last modified October 23, 2015, accessed March 11, 2016, http://education.nh.gov/standards/documents/ privacy.pdf.

25. Protecting Student Privacy Act of 2014, S. 2690, 113th Cong. (2014).

26. Kristin Yochum, “Protecting Student Privacy Act of 2014,” Flashlight (blog), May 16, 2014, http://dataqualitycampaign.org/ blog/2014/05/discussion-protecting-studentprivacy-act-of-2014/.

27. Corinne Lestch, “Louisiana Schools Struggle with Strict Privacy Law,” March 2, 2015, http:// statescoop.com/louisiana-schools-struggle-withstrict-privacy-law/.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. An Act Concerning a Comprehensive Review of the State’s Educational Data Infrastructure, and Making an Appropriation Therefore, CO. H.R. 07-1270, (passed June 1, 2007).

31. Fran Howarth, “Th e Role of Human Error in Successful Security Attacks,” September 2, 2014, https://www.securityintelligence.com/ the-role-of-human-error-in-successful-securityattacks/.

32. Adam Greenberg, “Info on Thousands of Chicago Students Posted to City Website,” SC Magazine (blog), December 6, 2013, https:// www.scmagazine.com/info-on-thousandsof-chicago-students-posted-to-city-website/ article/324470/.

33. Bill Fitzgerald, “Privacy Protection and Human Error,” Common Sense Media (blog), November 4, 2015, https://www. commonsensemedia.org/kids-action/blog/ privacy-protection-and-human-error.

34. Robin L. Flanigan, “Why K-12 Data-Privacy Training Needs to Improve,” Education Week, October 19, 2015, http://www.edweek.org/ew/ articles/2015/10/21/why-k-12-data-privacytraining-needs-to-improve.html.

35. “Maryland Longitudinal Data System Annual Report December 2012,” last modified December 12, 2012, accessed March 11, 2016, https://mldscenter.maryland.gov/egov/publications/MLDSC_Annual_Reports_2012. pdf; “Information Security and Privacy Policy,” last modified March 2014, accessed March 11, 2016, https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdereval/cdeinformationsecurityandprivacypolicy.

36. “Student Data Privacy Training,” accessed March 11, 2016, http://dpi.wi.gov/wise/dataprivacy/training.

37. Flanigan, “Why K-12 Data-Privacy Training Needs to Improve.”

38. Joanna Lyn Grama, “Just in Time Research: Data Breaches in Higher Education,” last modified May 20, 2014, accessed March 11, 2016, https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ ECP1402.pdf.