Previously published in the Seton Hall Journal of Legislation and Public Policy

III. STUDENT PRIVACY IN THE MODERN ERA

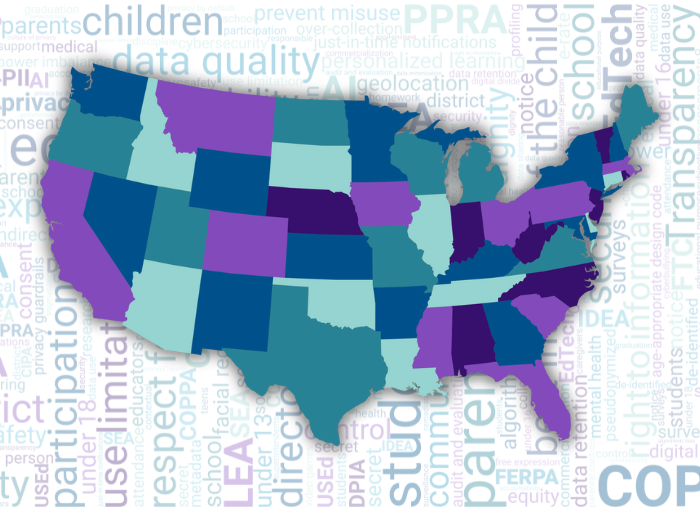

Forty years after FERPA was passed, more than 1,000 bills on student privacy have been introduced in all fifty states since 2013,106 and more than 130 have passed in forty states and Washington, D.C. Like FERPA, most of the laws emerged in response to growing concerns over the increased amount of student data collected but also how stakeholders use, report, and protect this data. Well-publicized data breaches in the private sector (such as at Target and Home Depot) lack trust in the government’s protection of privacy following the Edward Snowden leaks, and activists’ claims about FERPA’s insufficiency in the modern era fueled these worries and mobilized state legislatures to act. The result was a patchwork of legislative regimes across the country.

When legislators have passed these student privacy bills quickly and with little stakeholder input, they have brought unintended consequences to the students they sought to protect. For example, as detailed further below, the Louisiana state legislature passed a highly restrictive student privacy law that resulted in extreme such consequences.107 The law prohibited the state education agency (SEA) from collecting any student information; required parental consent for nearly all information sharing; and imposed fines and jail time on teachers and principals for all disclosure violations, even accidental cases. These stipulations prevented schools and the SEA from performing basic, necessary functions and prevented some students from accessing crucial benefits such as the state’s scholarship fund. In many ways, these consequences mirrored those that led to FERPA’s first amendment. In this section, we provide an overview of the current student privacy landscape and discuss four case studies demonstrating unintended consequences that resulted from new student privacy laws.

A. The State Student Privacy Landscape: 2014-2020

Since the 1800s, schools have collected data to monitor students’ progress, which has helped educators understand how to best serve their students. However, the increasing presence and sophistication of digital technology in schools since FERPA was passed have yielded significantly greater data collection. The passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2002 also began a new era of data collection.108 Suddenly, this well-meaning attempt to close the achievement gap required local and state education agencies (LEAs and SEAs, respectively) to report students’ progress and to track how schools were serving different student subgroups.109 Analysis of that data has resulted in substantial, useful findings. For example, a study released in 2016 revealed disproportionate suspension rates of minority students and that these students are routinely not referred to advanced placement classes.110

Education technology, or edtech, is now ubiquitous in the modern school system.111 In most schools, teachers use a learning management system to track attendance, lesson plans, and homework, and a student information system to access student records. Many middle and high schools issue laptops to all students and allow them to take the devices home. Students often use their own devices to work on assignments collaboratively inside and outside the classroom.112

In 2013, an edtech initiative called inBloom launched in order to improve data entry and storage in educational settings.113 With inBloom, teachers could better understand the data collected about their students and would no longer have to enter multiple usernames and passwords for each edtech tool used; student information did not have to be entered multiple times in every database; and parents could access their children’s records in one place.114 InBloom’s website advertised the company’s “world-class” security protections.115 States across the country raced to adopt the initiative because of inBloom’s potential value for teachers, students, and parents.

However, the publicity regarding inBloom drew public attention to how schools collected and used students’ data. Parents were shocked to learn that “schools [were collecting] hundreds of data elements, and [using] those to evaluate students unbeknownst to them.”116 Schools were also handing over that student data to third-party companies. In a case study of inBloom published in 2017, researchers noted that the tool “served as an unfortunate test case for emerging concerns about data privacy coupled with entrenched suspicion of education data and reform.”117 Stakeholders linked debates about increased standardized testing associated with Common Core curricula and teacher evaluations to data privacy issues, creating an incendiary environment that culminated in intense focus on inBloom and, ultimately, pressure on lawmakers to act.

Privacy activists who opposed the increase in sharing students’ data emphasized the risks of data use and technology, while ignoring benefits such as personalized learning. A parent advocacy group called Class Size Matters described inBloom as a company built to “collect, format, and share personally identifiable student data with for-profit vendors” to “help [these vendors] develop their ‘learning products.’”118 The Electronic Privacy Information Center, another advocacy group, raised concerns that inBloom could help create “principal watch lists,” allowing school administrators to surveil, label, and punish students with little procedural transparency.119 InBloom’s messaging did little to assuage the fears raised by parents and privacy organizations. The company’s website contained lists of data elements that districts could collect about students, and the security policy stated that the company could not “guarantee the security of the information stored” or that the information would not be “intercepted” when transmitted.120 This was a frightening admission to the many parents who were unaware that this language was standard in edtech companies’ privacy policies.121

Parents protested in states like Louisiana and Georgia, causing state leadership to cancel partnerships with inBloom, while other states publicly announced that they would evaluate the tool before moving forward.122 In seven months, inBloom’s nine state partners became three.123 By fall 2013, New York was the only state publicly moving forward with inBloom.124 However, in early 2014, the New York state legislature included a clause in its budget “making it illegal for the state to share personally identifiable student data with any shared learning infrastructure service provider via a private, cloud-based, or state operated student datastore,” banning schools from using services such as inBloom. InBloom shut down in May 2014.125

However, inBloom’s demise did not eradicate the public’s fears about student privacy, in part because school districts and edtech companies overall were unprepared to respond to activists’ privacy concerns. Mostly for the first time, schools were asked to justify the data they had been collecting and to explain their processes for protecting that data. Almost no state or district knew how to answer these questions. In this vacuum of silence and confusion, activists presented frightening what-if privacy scenarios to motivate parents to push for new legal privacy regimes, and the media continued reporting these issues through 2014 and 2015. Some articles claimed that “[t]he NSA has nothing on the ed tech startup known as Knewton,” using alarming imagery such as “data mining your children” and “monitoring every mouse click.”126 A New York Times opinion piece headline declared that “Student Data Collection Is Out Of Control.”127 An NPR Marketplace report described, “A day in the life of a data-mined kid,” in which students carry identification cards installed with radio frequency identification chips that track their every movement.128 Parents quoted in these articles worried that the data collected would affect their children’s future college choices and job prospects.

In this context, parents’ fears regarding the collection and use of their children’s educational data are understandable, and some stakeholders mobilized these fears to persuade legislators. One expert made a widely reported statement at a congressional hearing, stating that only seven percent of school contracts banned outside vendors from selling student information, without noting that the seven percent cited was made up of a subgroup of less than ten districts.129

Legislators responded quickly to stakeholders’ concerns, introducing 110 student privacy bills in thirty-nine states in 2014 and 180 student privacy bills in forty-nine states in 2015.130 By the end of 2019, states had passed more than 130 student privacy laws in forty states and Washington D.C.131 These states have reacted to irresponsible student data practices and their constituents’ outrage by passing laws intended to protect students’ privacy. However, some state legislatures did not fully appreciate how these laws would impact day-to-day instruction in the digital classroom.

Unintended consequences have often resulted from laws written with vague or sweeping language, harsh penalties, and no consultation with the stakeholders who implement the laws. For example, if a policymaker asked constituents whether they would ban the sale of all student data, the likely response would be overwhelmingly positive. Yet, as described further in the case studies below, an outright ban with no exceptions would prohibit schools from offering yearbooks, class photos, and PTA directories. Most policymakers seek to carefully balance crucial protections for students with allowances for responsible data use, to avoid banning useful practices. Yet, the overheated privacy debate resulting in unbalanced legislation has fueled deep distrust among education stakeholders, with far-reaching effects. Parents have struggled to understand how schools use and protect their children’s information; edtech providers have struggled to develop their products and services and, in some cases, even operate; administrators, educators, and researchers have struggled to gather students’ information needed to improve schools and students’ achievement. To achieve promising educational innovations such as personalized learning, student privacy laws must improve, along with public perception and privacy practices on the ground. The following four cases illustrate unintended consequences resulting from hastily passed, reactive legislation intended to protect students. The cases can also help policymakers craft laws that make privacy a part of stakeholders’ use of student data, rather than an impediment to that use.

B. Louisiana

Louisiana’s student privacy law, one of the strictest in the nation, took effect in 2015.132 The bill intended to ease parents’ concerns by ensuring protection of students’ data and providing transparency to parents about data sharing practices with school vendors.133 However, the original law’s opt-in consent requirement for sharing student information, vague wording, and strict interpretation led to several unintended consequences.

Some of the law’s other unintended consequences emerged when St. Tammany Parish School District implemented the law in full before the legislation’s original effective date.137 State Representative Schroeder, whose district included St. Tammany Parish School District and who later introduced legislation to amend the original law, noted that “some of the unintended consequences are you can’t hang art on a wall in the schoolhouse without taking the name out, you can’t do a newsletter and have kids names on it, so we were running across problems with just ID cards and cafeteria cards.”138 In the Franklin Banner-Tribune, a school board legal advisor said that the Louisiana law meant that “[w]ithout that [written parental] approval we would potentially be in violation of the law by publishing names and photographs in yearbooks, in football programs, students of the month, the honor rolls, etcetera.”139

Another consequence resulted from the provision to increase transparency regarding data sharing. The provision required schools to publish on their websites their vendor contracts and the third parties with which schools shared data.140 As a result, the provision made students’ data potentially less safe. Louisiana School Boards Association attorney Danny Garrett explained, “What we had inadvertently done is we had created a roadmap for people who were going to try to access that data, because they could go on the school system’s website, see what vendor had what types of data, and then they could go and attack that vendor.”141

Louisiana passed HB 718 on June 23, 2015, to address some of these unintended consequences and clarify the legislative intent.142 The amendment allowed any district to pass a policy with less-stringent privacy requirements.143 This resulted in multiple different versions of student privacy laws varying by district, which still exist today.144 However, the amendment retained several of the original legislation’s extreme requirements. Both versions of the Act do not allow the state Department of Education to receive personally identifiable information, instead requiring the department to create a unique identifier for each student.145 The law’s strict penalties, a $10,000 fine and up to six months in jail per violation, also remain.146

C. New Hampshire

In 2015, New Hampshire passed a student privacy law that prohibited schools from recording in classrooms “for any purpose without school board approval after a public hearing and without written consent of the teacher and the parent or legal guardian of each affected student.”147 This meant that New Hampshire school officials needed to hold a public hearing, obtain school approval, and receive written consent from all affected teachers and parents before recording could take place in classrooms.148 The law complicated the teacher certification process, which often requires recording teachers in order to evaluate them.149 The law also conflicted with the federal law mandating accommodations for students with disabilities, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).150 In response to confusion over how districts should proceed under the state law, Heather Gage, of the N.H. Department of Education, stated in November 2015, “You need to continue to provide services for special education, as mandated by federal law.”151 For example, video recording is often used as an accommodation for students with ADHD; one website discussing video recordings’ many uses in the classroom provides that “[i]ncorporating videos into lessons offers a viable method for students with special needs, such as ADD/ADHD or conditions requiring home-bound stints, to retain and remember information. The medium makes for one more way to ensure all learners enjoy access to educational materials that meet their specific requirements.”152

The N.H. School Boards Association and the N.H. Department of Education issued a technical advisory regarding the law’s requirements in October 2015.157 This feedback led to an amendment in the next legislative session, which narrowed the statute’s language and clarified its intent.158 The 2016 amendments, HB 1372, clarified that nothing in the act prohibits recording or requires public process and written consent for students with disabilities and for instructional purposes.159 These amendments also allowed recording for teacher evaluations but retained the original requirements, including a public hearing, school board approval, and opt-in consent of each affected teacher and each student’s parent.160

This restriction on video recording for teacher certification is particularly onerous for teachers and administrators if they cannot obtain all parents’ opt-in consent, because certain certification organizations require video recordings as part of the certification process.161 An information privacy principles report published by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) states, “[c]lassroom video is an essential part of performance assessment because it captures teacher candidates as they deliver instruction and interact with students.”162

Moreover, for decades, the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards® “certification of accomplished teaching” has emphasized teachers’ ability to describe, analyze, and reflect upon videos for their own teaching practices.163 Researchers have also found that video recordings used for teacher evaluations often require less time and resources, compared to in-person observations, and are perceived to be less biased.164 A study commissioned by the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University found that, “[r]esearch about video observations provides a very clear message—teachers perceive the process as more fair, useful, and satisfactory compared to in-person observations.”165 Despite this widespread professional support for classroom recordings to evaluate and improve teaching, the stringent requirements for video recordings were still in place in 2020.

D. Connecticut

Connecticut passed the Student Data Privacy Act in 2016166 and amended it in both 2017167 and 2018168 to address unintended consequences. Stakeholders believed that the 2016 Act required a contract between local boards of education and anyone with whom the district shared student data.169 This meant that if only two students in an entire district used a certain software for an IEP or class project, the district had to complete a contractual agreement with the vendor, binding it to Connecticut’s privacy law.170 This resulted in excessive time, money, and resources expended to effect these contracts.171 Connecticut Association of Schools Executive Director Karissa Niehoff stated in written testimony to the Joint Education Committee on March 14, 2018, “One district technology director calculated that PowerSchool (the most common data platform in schools) has over 160 individually negotiated contracts with exactly the same language. If a district has [thirty] (low estimate) apps and software packages that use student data, this suggests that there are nearly 5,000 individual contracts that need to be negotiated across the state.”172 Doug Casey, Executive Director of the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology, wrote in an article about the Act that, “Having 169 districts and thousands of technology companies separately interpret and act on our state’s student data privacy law. . . has proven hugely time-intensive, duplicative and inefficient.”173 To address the time and resource burdens placed on districts, the 2018 amendments allowed state-level negotiations of contracts with vendors through a uniform student privacy terms-of-service addendum.174

In some instances, districts were unable to reach an agreement with a vendor, which meant foregoing beneficial software.175 For example, Monroe Schools Assistant Superintendent Jack Zamary said, “When you get into sophisticated applications at the high school level, for Advanced Placement courses, the software that’s used at that level is very professional.”176 While companies, such as Google, have changed their terms of service to comply with the Connecticut law, Zamary said that some companies are not willing to change their terms because the Connecticut school market is too small,177 and “it really puts us in a very awkward place . . . [b]ecause our kids love the course, they love doing the work, but we’re having a real challenge getting compliant software to offer that kind of course.”178

The 2016 law also imposed a strict notification time frame, requiring personal notice to all students and parents within five days of any contractual agreement with a vendor that handles student data.179

The Act was amended in 2017 to give districts and vendors more time to comply with the law, by moving its effective date to July 2018.182 Joseph Cirasoulo, Executive Director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, said at the Joint Standing Committee hearing on March 6, 2017, “I also don’t think that any of us fully understood the implications of the Act once it got down especially to the classroom level and that’s why we’re back asking for a postponement, relooking at it, revising it, so we can protect the data and the privacy of the date (sic) and also allow for things to go on in the classroom that should go on.”183

The Act was amended in 2018 to further address consequences that the 2017 postponement and amendments had not fully resolved.184 These amendments partially addressed the contract negotiation burdens by allowing the Connecticut Commission for Educational Technology to create “The Hub,” an online database that allows educators and school administrators to quickly search and identify companies that have signed Connecticut’s Student Data Privacy Pledge and have agreed to comply with Connecticut’s Act.185 Most significant, the 2018 amendments also created an exception to the requirement for written contracts for each vendor, for vendors used for IEPs that are “unable to comply with the provisions of this section.”186 Doug Casey stated in his 2018 written testimony to the Joint Education Committee, “The Student Data Privacy Act was never intended to deprive a special education student from being able to access a particular resource needed to fulfill his or her individualized education plan.”187 While a prior version of the amendment limited the special education exception only to vendors providing services or products used by two or fewer children per district, some school officials, such as Amity Regional School District No. 5 Superintendent Charles S. Dumais, felt that this did not go far enough and called for a complete exception regardless of the number of students.188 The 2018 amendment states that if a vendor meets the student IEP exception, the vendor still must have attempted to create a contractual agreement with the school board, the school board must have researched and failed to find alternatives that would comply with the Act, the parent must give written consent, and the vendor must still comply with the Act’s use restrictions.189

The Act’s amendments also relax some of the notification procedures.190 Instead of requiring individual notice of each vendor contract, schools instead must post on a website notices of the contracts within five days of having reached the agreement.191 Schools must provide to parents, before September 1, each year, the website address where the notices are posted.192 The amended Act also extends the breach notification time frame to two business days instead of forty-eight hours, but still does not address breaches that have not been patched or cases in which the affected students are unknown.193 The Joint Education Committee report for the 2018 amendments demonstrated continued overwhelming support for the Student Data Privacy Act, but many of the public comments asked for the legislature to not delay the Act’s implementation any longer.194 The 2018 amendments were passed on June 7, 2018, with most of the provisions becoming effective as scheduled on July 1, 2018.195

E. Virginia

Virginia provides another cautionary tale in which lawmakers enacted student privacy legislation as a swift reaction to isolated incidents. In 2018, Virginia passed a law to limit the sharing of student directory information, especially student emails, phone numbers, and addresses, and the law was subsequently amended in 2019 to eliminate unintended consequences.196 The original bill emerged in reaction to the actions of a progressive political group, NextGen, during Virginia’s 2017 State Elections.197

NextGen obtained college students’ cell phone numbers through a Virginia Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request served on various universities, and then texted students to encourage them to register to vote and to vote and volunteer for progressive candidates.198 After NextGen’s actions gained the attention of collegiate and local news media, Virginia House Delegates Tony Wilt and Joseph Yost discussed introducing legislation in the subsequent term to prevent this sort of data sharing in the future.199 Both Dels. Wilt and Yost faced Democratic challengers who received campaign contributions from NextGen, and Wilt’s challenger, Brent Finnegan, was one of the candidates that NextGen had encouraged students to support in the organization’s text messages.200 Del. Yost was ultimately defeated by his challenger, but Del. Wilt was re-elected, and prefiled HB 1.201

HB 1 sought to modify the directory information section of the Code of Virginia, by requiring schools to obtain opt-in consent from students, or parents of students under age eighteen, in order to ever disclose directory information to others, including

disclosure through a FOIA request.202 In addition to HB 1, Del. Chris Hurst, who defeated Joseph Yost for the Delegate seat in the 2017 election, also introduced a bill in light of NextGen’s use of student directory information. Hurst’s HB 147 sought to add one sentence to Virginia’s FOIA Scholastic Records exemption, to exclude students’ cell phone numbers and email addresses from FOIA’s mandatory disclosure.203

In the Senate, Sen. Suetterlein introduced a bill, SB 512, requiring educational institutions to obtain written opt-in consent before sharing students’ addresses, phone numbers, and emails pursuant to FOIA requests.204 Hurst’s bill was passed by a House subcommittee, but was left in the general House without further consideration.205 Wilt’s HB 1 passed the House, but the Senate voted to substitute HB 1 for Suetterlein’s bill, SB 512.206 The House rejected this substitution, and a conference committee was convened, which ultimately resulted in the passage of HB 1 and SB 512 in both houses.207 Gov. Ralph Northam signed both into law, and they became effective July 1, 2018.208

Together, the laws required schools to obtain opt-in consent from students not only when sharing students’ email addresses and phone numbers pursuant to FOIA, but for all sharing of directory information.209 The bills’ passage made Virginia the first state to adopt an opt-in regime for sharing directory information, as other states and FERPA mandate an opt-out regime whereby schools notify students and parents of what constitutes directory information and give them the opportunity to opt out of the schools’ sharing of this information.210

From the outset, even prior to the law’s passage, some stakeholders were skeptical of HB 1’s broad scope, calling it a “sledgehammer” when compared to HB 147, which was perceived to be a “scalpel.”211 Some interest groups, such as the Virginia Coalition for Open Government, also opposed the bill.212 When the 2018 school year began a few months after the July 1 effective date, stakeholders immediately noticed the law’s unintended consequences. Since the initial legislation was prompted by FOIA requests gone wrong and only public institutions are subject to FOIA requests, some private universities assumed that the law only applied to public institutions.213 For example, the general counsel of University of Richmond, a private institution, tracked the bill from its introduction through passage but did not express opposition because she did not think the bill would apply to the University of Richmond.214

After stakeholders realized the scope of the legislation, universities pulled their student directories from both their public and internal websites so that third parties and other students could no longer locate other students’ email addresses.215 A statement by the VCU Office of the Provost read, “Students will no longer be able to find contact information for another student through phonebook.vcu.edu or the people search on the VCU website.”216 The same office also stated, “University online applications— such as Blackboard, email, room reservation systems and Service Desk— will no longer enable non-employees to search for student eID and email addresses, including the auto-complete feature of email addresses currently used in many systems.”217

Students and educators also found it more difficult to work on group projects and to collaborate with classmates because institutions interpreted the bill as prohibiting professors from sharing students’ email addresses with other students.218 University of Richmond Registrar Susan Breeden said, “I think the hallmark of a Richmond education is the collaboration, and it just makes it harder.”219 Some professors anticipated these issues and required students to opt in to data sharing early on in the semester. “In one of my first classes this semester, my teacher made it clear for us to go into myVCU and give the university permission to share contact information in order to make class communications easier,” a VCU student stated.220 Student journalists were also concerned about the “dangerous precedent” that HB 1 could set for obtaining student information from FOIA requests.221 Student Press Law Center Senior Legal Counsel Mike Hiestand stated, “This is really the nuclear option for public records.”222 When stakeholders began to feel the law’s unintended effects, reports surfaced that certain university registrars sought amendment of the statute when the legislature reconvened.223

As a result, Del. Wilt introduced HB 2449 to amend his original bill.224 Wilt explained, “My intent from the very beginning was not to place a hardship on the schools. The real goal was to prevent outside people, whoever they may be—political groups—completely unrelated to the school, being able to access students’ most intimate information for their own purposes.”225 HB 2449 created an exception to the opt-in requirement for directory information when information is shared internally with other students or with school board employees.226 These changes alleviated concerns among university professors regarding sharing students’ contact information with other students, and among university contractors and vendors.227 Governor Northam signed HB 2449 into law on March 5, 2019.228